Were There Black People in Britain During The English Civil War? (erm, yes!)

During the post Roman period there is little evidence or records of the existence of Black Britain’s but you can assume that any Black Romans left behind will have had mixed marriages and the origins would have dissipated over the generations.

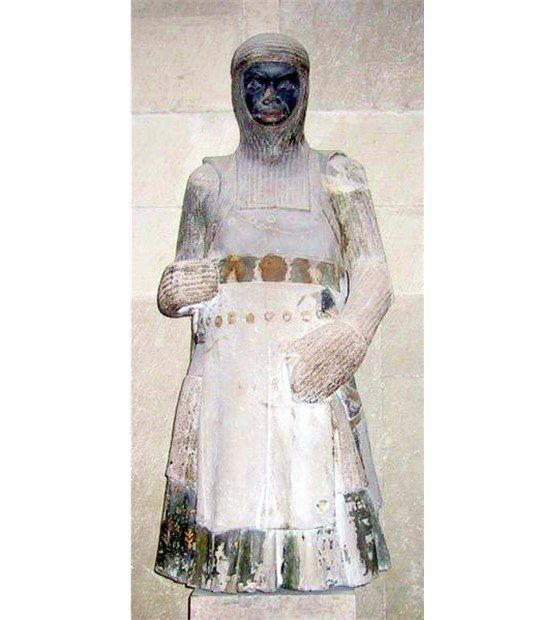

However during “The Dark Ages” leading into the early medieval period with the growth of Christianity, a Black Roman commander born in Thebes, Egypt about 250AD was venerated in 926AD. St Maurice led a Roman Legion of 10,000 Christian troops and was executed along with many of his Legion for not butchering Christians when ordered to do so by the Emperor.

During the Medieval period, there was increased trade with Africa, no doubt Black sailors and tradesmen would not have been uncommon at major ports around the coast of Britain.

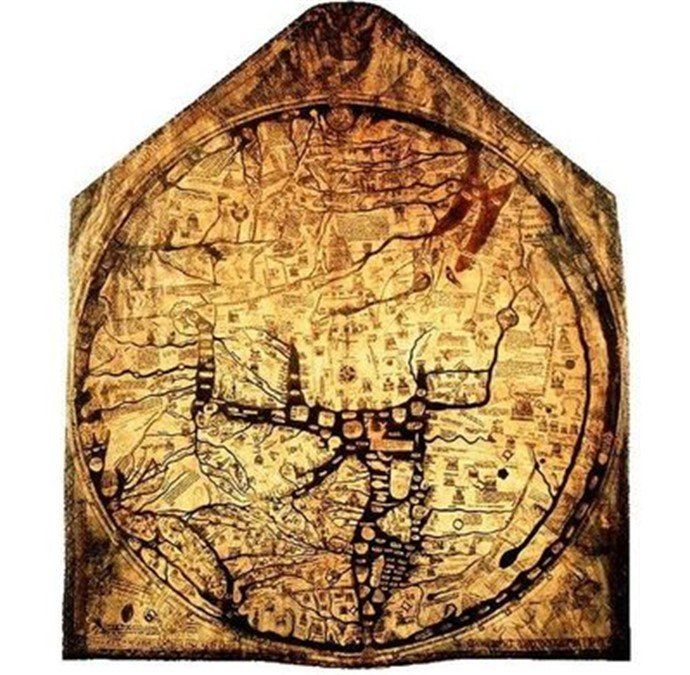

The Mappa Mundi (circa 1300) clearly shows three distinct Christian continents of the known world, Europe, Asia and Africa with Ethiopia as the heart of Christian Africa. Africa was seen in Medieval Britain as a very rich and plentiful continent with strange and exotic animals and mystical human entities.

The Moorish invasion of the Spanish peninsula didn’t enhance the standing of many Black people in Europe as a whole but there is plenty of evidence that Black soldiers were employed in many armies throughout the continent. When the Moorish forces were driven out of Southern Europe not all the Moors who have headed back to Africa but many came north through France and up into Northern Europe.

With Britain entering the Tudor Age, we see the country entering a period of sustained growth of its Black population and clear evidence starts appearing again.

Catherine of Aragon, future wife of Henry VII came from Spain to Britain with at least one Black woman in her entourage, known as Catalina de Cardos and was important enough to be given the role of Head of the Bed Sheets. She may have been involved in proving that Catherine’s doomed first marriage to Prince Arthur had not been consummated ahead of her marriage to Henry in 1509.

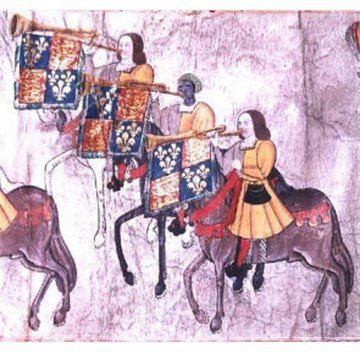

In 1511, King Henry VIII held the Westminster Tournament at which his Royal Trumpeters performed and in painting celebrating the event we clearly see a Black trumpeter. His name was John Blanke, probably came to this country as part of Catherine of Aragon’s entourage and first employed by King Henry in 1507.

John Blanke was involved in what we would today describe as an employment dispute as he brought a grievance against the King as he was being paid less than his White counterparts. Unlike many who stood against Henry, John Blanke was successful and received an increase in his wage to bring up to parity with his white colleagues.

When John Blanke married in 1512, the King presented him with “a gown of violet cloth and also a bonnet and a hat to be taken of our gift against his marriage” so we can assume he was highly respected by his employer. Again in a painting of The Field of Gold from 1520 there appears a Black Royal Trumpeter who it is assumed was John Blanke still in the King’s employment.

Black people were coming to this country during early Tudor period and being employed as musicians, dancers, entertainers and domestic servants. Most were to be found in and around the major southern ports like London, Southampton and Bristol but not exclusively.

Specialist workers were being brought into Britain, in 1545, King Henry VIII hired a Venetian Salvage Expert, Corci, based in Southampton where he worked with the Italian traders when their boats were lost coming into harbour. Henry had lost his flagship, the Mary Rose in Portsmouth harbour and wanted to recover his ordinance from on board and Corci’s lead diver was Jacques Francis who originally came from a small island off the coast of Guinea where pearl and fishing divers were employed by Europeans for their swimming and diving skills.

We know a reasonable amount about Jacques Francis as he was the first Black Man to appear in court records when he gave evidence on behalf of his employer, Corci, when he was involved in a case where he had been accused of theft from a clients ship.

Trade with West Africa continued to grow throughout the 16th Century but it was during the Elizabethan period where Britain saw a big increase in the numbers of Black Africans coming to our shores. As Britain’s trade grew, we saw conflict with the traditional partners, namely Portugal and Spain with Queen Elizabeth’s “Privateers” such as Drake, Hawkins and their like regularly raiding Spanish and Portuguese trade ships going from the Spanish mainland to West Africa and then over the Atlantic Ocean to their colonies in The America’s.

As well as gold, ivory, spice and exotic African goods, the Privateers were taking the African slaves from the Iberian ships who along with the rest of their bounty were brought back to Britain.

Generally speaking these poor souls were either released on the docks of port cities like London, Southampton and Bristol to fend for themselves or as local people realised there was a regular supply of Black workers, they would offer the ship Captains a fee to take them off their hands.

These were not classed as slaves as we would later recognise but like anyone, regardless of race in this time who was penniless, homeless and disorientated by their dreadful experience they would have had a difficult time however learning the language and more importantly becoming a Christian would see their lives improve. The first Black worker in the port city of Bristol is found in 1560 when Sir John Young employed a African straight from the ships to work as a gardener in his grounds located just behind what is now The Red Lodge Museum.

Most Africans were to be commonly found in and around the port cities generally employed as domestic servants, musicians, entertainers, sex workers and low level tradesmen. Most common though was likely to be sailors on trade ships

The subject of slavery is one that can’t be ignored, generally speaking slavery didn’t exist and Queen Elizabeth described the trade as “detestable and would call down the vengeance of Heaven upon the undertakers”. However some Royal loans could be linked to small scale slave trade operations. The only commercial slave trade during this period was linked to Sir John Hawkins who made four trips from West Africa to The Americas before ceasing the trade. He saw the financial opportunity follow numerous successful raids on Spanish ships filled with African slaves bound for their colonies.

In 1596, following successive failed harvests and subsequent food shortages, Queen Elizabeth wrote to the Mayor of London & other leading Aldermen around the country expressing concern over the increased numbers of Black people in the country and suggesting they should be deported. Showing the value employers regarded their Black workers and their embeddedness into society, only 10 were ever deported.

Reflecting how Black people were an intrinsic part of Elizabethan society, we just have to look at the writings of Shakespeare whose plays had a number of important Black roles such as Othello based it is believed on his Black mistress’s father and Caliban from the Tempest.

In the previous article, we looked at how Black Africans had been an important part of society for 1500 years leading up to the 17th Century and the English Civil War.

The beginning of the 17th Century saw significant changes in Britain with the Tudor dynasty making way for the Stewarts with James VI of Scotland coming south to take the crown from the deceased Elizabeth.

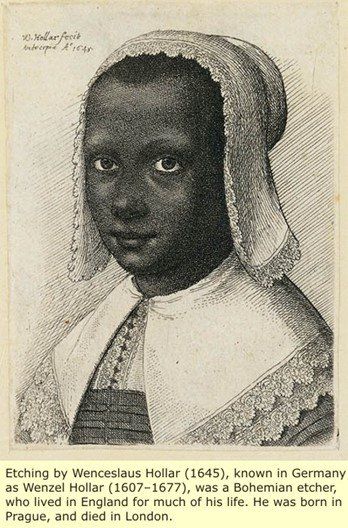

With James and his royal entourage arriving in London there is evidence of a small but significant number of black domestic and personal servants. Black servants were seen as a very fashionable thing to have throughout Europe’s elite and these people would have been richly attired to show off their existence. In addition to the servants, high society entertainment would very often involve Black musicians, dancers, acrobats and entertainers.

On the birth of his first son, Henry, James VI held what described as a magnificent pageant with the centrepiece being a famous Black entertainer playing the part of a ferrous lion who was described as being “Black-Moor and very richly attyred”

King James with his richly attired Black servants would have set the present for his courtiers to follow the fashion and no doubt as the middle classes grew in financial strength they too would have wanted to be seen as having Black domestic servants.

Not all Africans in Britain would be in service; again in Bristol, a barmaid called Katherine worked at The Horses Head in Christmas Street until her death in 1612.

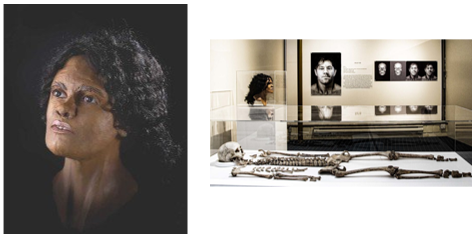

A self sufficient Single woman described as a “negra” (a Black Woman”) called Cattelena of Almonsbury near Gloucester appeared to make a living from the proceeds of the products from her cow and provided food for travellers passing through the town. Records show clear evidence of 50 other independent Black women between 1571-1640

Parish records from the 17th Century show evidence of Black residence in Cornwall, Devon, Somerset, Wiltshire, Gloucester, Kent, Northampton and Suffolk although London appears to be the main location for the Black community. In 1610, ships records show up to 30% of ships crews were Black African sailors but also others from Japan and Asia

In 1618, the Thirty years War broke out in Europe and it is estimated that up to 50,000 refugees fled to Britain with London being the location of choice especially for professionals and skilled tradesmen from the Low Countries.

Many of these new citizens would have brought their domestic servants with them and considering that Holland and especially Antwerp where many of them had fled from had the second largest population of Africans (Lisbon being the largest as the capital of the European slave trade) in Europe.

A census in the early part of the 17th Century in Southwick, a very poor South London borough with a total of 20,000 inhabitants (10% of London’s total population) had 2004 “alien” households representing 10% of the boroughs population.

Parish records in London from this period show regular Black inhabitants getting baptised, married and buried. It is interesting that it appears that the majority of Black men marry white British women and therefore it is safe to assume that there was a significant population of mixed race people growing up in the 17th Century

As we move into the middle of this century there is evidence that a lot of Black residence of London have taken on specialist trades and records show involvement in needlemakers, seamstresses, milliners and silk work. Many of these had learnt their trade from being servants from Holland who took over from their employer following their death.

Not everything was positive with the relationship between Britain and the relationship with Black Africans. In 1610 James I granted a license to set up the Guinea Company who primarily traded in gold but it is believed they did get involved in low volume slave trading in 1619 (Virginia, US) and 1626 (St Kitts). In 1631 King Charles I grants a monopoly to this company for sole trade between Guinea and London.

With the increase in trade came far greater travel and access to Africa and many of the explorers were far from complimentary about what they found especially being derogatory about the inhabitants of the continent that challenged the beliefs and values of Protestant Gentlemen of the time.

Sir Thomas Herbert in 1627-9 described the Africans as “fearful blacke….devilish”, devils incarnate” and “worshipped the Devil”. In 1634 Herbert wrote “Comparing their limitations, speech and visages, I doubt many of them have no better processors than monkeys” and also implied that they copulated with Apes and told stories of Baboons raping Black women.

William Bosman described Africans as “Nothing but the utmost necessity can force them to labour, they are besides incredibly careless an stupid”

There are many such extracts from travel writers of the time and none paint positive pictures of the inhabitants of Africa and the influence of these writings on those in Britain reading them would no doubt had a negative response to those Black inhabitants of Britain

Any suspicion or negativity towards the Black population would not have been helped by continued raids on the coastal towns of the South & West of Britain by those known as the Barbary Pirates.

These North African pirates generally speaking were linked to trade with the Ottoman Empire and spread terror throughout the coastal settlements of Europe. In 1626, it was estimated that there were up to 60 Barbary men-of-war ships prowling the coastal waters of Devon and Cornwall looking for boats and ships to attack or unprotected coastal towns and villages to raid. As well as looking for ships and there contents, the Barbary Pirates would take entire populations of towns and villages to be sold into slavery in the Ottoman Empire. In 1645 it was estimated that there were between 3000-5000 English slaves in Algiers.

The traditional view that there were no Black people in Britain during the mid 17th Century is clearly inaccurate however there is little evidence of Black soldiers being directly involved in the Civil War in any great numbers

In 1643, the Parliamentarian leader, the Earl of Stamford was accused by the Royalists “when the Earl of Stamford was last at Exeter he took divers, Turks out of Launston gaol and listed them for the King & Parliament”. There is evidence of a “Turk” (another name for a North African/Barbary Pirate who was potentially Black) serving in the Exeter garrison alongside a range of other ethnic groups in its Parliamentarian ranks

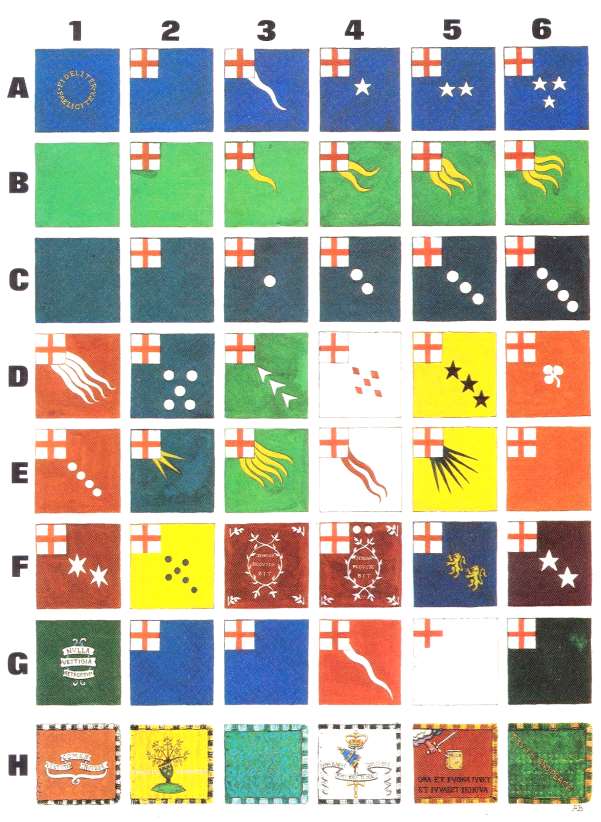

General Massey’s Western Brigade was said to include “Ethiopians, Egyptians and Mesopotamians” when it was disbanded in 1646. Evidence in the records that Black soldiers in Massey’s Brigade were given passes to leave Britain suggests that they were very likely to have been paid mercenaries rather than settled men from this country.

Bearing in mind the clear evidence that anything up to 30% of sailors in the fleets around Britain were of African descendency, it is safe to assume that when the military fleets were formed during the Civil War that they would have called upon the skilled and experienced Black sailors that were available. The small Royalist fleet in Bristol in 1643 was reported to have twelve Black sailors in its midst

The Royalist commander of Cheshire, Lord Byron argued that Royalists should actively recruit from all nations “I know no reason why the King should make any scruple of calling in the Irish or the Turk if they should serve him”.

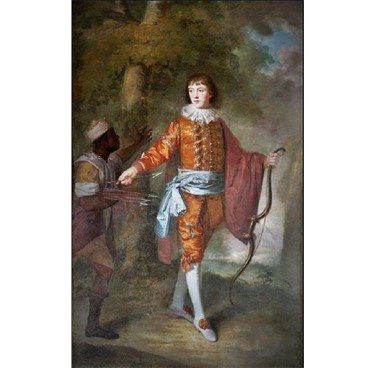

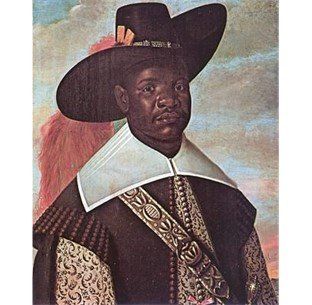

Byron is pictured with his young Black squire as indeed was King Charles himself.

In summary, there were a significant number of Black people in Britain during the time of the English Civil War especially in London and the port towns of the South and West coast of Britain.

Primary occupations for these people were sailors, domestic servants, musicians, entertainers, skilled tradesmen/women, entrepreneurs, single women and sex workers

There were Black men directly involved in the War being in both navies and soldiers especially in the west Country although you do question that with the significant numbers based in London during the middle of the century that there were not Black soldiers involved in the formation of the London based Regiments but evidence hasn’t been found yet to my knowledge.