Archery in the English Civil War

The nature of Neade’s now famous invention appears at first glance to be something of a novelty rather than a practical proposition for use on the battlefield. However, we know it worked as Neade himself made it work and he persuaded the Artillery Company of London to put it into practice. In March 1628 the Council of War gave orders for a formal trial of Neade’s idea and 300 members of the Artillery Company turned out in St James’s Park in London to demonstrate it in front of King Charles I. In fact Charles himself had a go and was impressed enough to commission William Neade and his son to provide training and instruction to the county militias in the use of the double armed soldier.

William Barriffe wrote of it: “In all these firings, the pike never come to charge, but stand in a square battell, in danger of the enemies shot: themselves neither being able to offend the enemy nor to defend themselves. And yet if by frequent practice, they were inured to the use of the longbow, fastened to their pikes, I made no question but that, when they should become expert in the use of the Bow and Pike, they would not onely be a terror to their enemies, by the continual showers of Arrows which they would send amongst them; but also that they would be a great meanes to rout their enemies. And utterly to breake their order”

Robert Ward in his Animadversions of Warre (1639) and Sir Thomas Kellie in his Pallas Armata (1627) were both keen advocates of Neade’s double armed man and this was part of a much large attempt to revive the use of the longbow during the first half of the seventeenth century. In 1631 and in 1637 King Charles I reissued the statute of 33 requiring all men between the ages of 16 and 60 to both own and practice with the longbow.

The most significant attempt to reinstate the longbow came in 1627 when King Charles’s favourite councillor, the Duke of Buckingham raised an army to attack the Isle de Rhe in support of the French Huguenots at La Rochelle. Orders from Buckingham were sent out to the counties for the levying of men and it was stipulated that 24% of them were to be archers. In some counties the order for archers arrived too late and the force had already set off for the embarkation points and in other counties not enough archers could be found to fill their quota. Nevertheless bows and arrows were ordered from the Tower and archers were reportedly assembling at Portsmouth but exactly how many made it to France is unclear but French sources reported arrows being shot into the fort of St Martin de Rhe.

In many years prior to the civil war there were plenty of longbows in circulation and not just a few archers. With 300 men trained in the use of the pike and longbow in London and given William Neade’s commission from the King, it is reasonable to suppose that at least some trained with them throughout the provinces. Several hundred archers at least had been assembled for the expedition to Isle de Rhe and by recently enacted law every man from 16-6- had to own and practice with his longbow. Although we can assume not everyman in every part of the country observed the law it would be safe to assume that there were significant numbers out practicing on a regular basis. But does that therefore lead to significant numbers of archers taking to the field during the Civil War? No it doesn’t seem to mean that but before dismissing the use of the longbow completely E T Fox does provide us with some interesting evidence.

In the period leading up the beginning of the outbreak of the war, King Charles issued Commissions of Array ordering his supporters to raise troops in their locales for his service and they included provision for archers. The Commission sent to the Marquis of Hertford, for example, to raise troops in the West Country and Wales instructed that he raise an army consisting of “Horsemen, Archers and Footmen of all kinds of degrees meet and apt for the Wars” Indeed this Commission included Hereford, one of the counties where there was a company of archers in 1642 according to JW Willis Bund his book The Civil War in Worcestershire 1642-1646.

During the same period, a company armed with pikes and longbows in Hertford specifically for defence of the town when they believed the town was under threat of attack from a Royalist force. The local Parliamentarian commander, Earl of Bedford sent a party of cavalry under Captain Ankle to boost the defence of Hertford and when they approached the town they were met with piquets posted on the outskirts of town but having given the password they were admitted. Ankle’s cavalry were then met by “a second watch, being a company of pikes with bowes and arrows”.

Another company of archers was raised on behalf of Parliament in Shropshire, troops stationed in Bridgnorth were expecting the arrival of the Earl of Essex when instead a Royalist force under Prince Maurice arrived. Cavalry were sent out but a large force of Royalist musketeers under Lord Strange took up position just outside the town and drove the cavalry back. Fearing that the triumphant Royalist would drive home their success by fording the river and enter the town, the defenders “with …..Bowes and Arowes sent to them which did so gaule them, being unarm(our)ed men that with their utmost speed they did retreat”.

In the earl months of the War there is evidence of formations of archers being assembled and in at least one cased, used in action during the defence of towns. Archers may have been a reasonably common feature of sieges on both sides of the conflict. At the siege of Gloucester in 1643 bows were used to shoot messages in and out of the besieged city and according to Peter Gaunt in his book English Civil War, a Military History, messages were shot by longbow into Basing House by Parliamentarian besiegers in 1644.

Also at the siege of Lyme Regis, Dorset the Royalists shot fire arrows into the town and set alight to the a good number of buildings and there is additional evidence of arrows being used for sending messages as late as 1648 in the sieges of Colchester and Pembroke.

Locally raised companies of archers raised to defend their towns or what might be only one or two archers present at sieges are not the same as formations of archers being active in the field armies though no less important. In September 1643 the Parliamentarian newspaper Mercurius Civicus reported the news from Oxford that the Royalists:

“have set up a new Magazine without Norgate, onely for Bowes and Arrowes, which they intend to make muchuse of against our horse which they heare (though to their great griefe) doe make much increase: and that all the Bowyers, Fletchers and Arrow head makers that they can possibly get the imploy and set on worke there for that purpose. Also that the King hath two regiments of Bowes and Arrowes. It is therefore necessary, that no Arrow-heads be suffered to goe from London towards Newbery, or into any other parts where the Cavaliers may by any means come to achieve or surprise them. And it were to be wished, that the like provision were made by the Parliament here to get bowes and Arrowes (at least some for their Pikeman) it being not unknown what victories have been formerly atchieved in France and other parts by our English Bow-men> Besides the flying of the Arrowes are farre more terrible to the horse then bullets and doe much more turmoyle and vex them if they enter”

That the king had two regiments of archers is unlikely but that fact that it was printed in 1643 indicates that it was not considered unlikely at the time and the fact that the movement of arrowheads was to be restricted suggests that there was at that time a supply worth restricting, The most intriguing thing perhaps about this article is that the bows and arrows were for supplying the pikemen thus suggesting that the double armed man was still considered a possibility in 1643 and may have been what was meant by the ambiguous reference to the “company of pikes with bowes and arrows” in Hertford in the previous year.

Importantly, the rallying cry of Mercurious Civicus for a Parliamentarian force of archers was heard in the highest circles. Thomas Taylor served as a lieutenant under Colonel Fiennes at the Siege of Bristol and was called as a witness by Fiennes to appear at his trial for surrendering the city too early. When he first gave his deposition he was a lieutenant but by the time of the trial itself he had been promoted to Captain. As well as his promotion, Taylor was also given his own command:

“Whereas, by Virtue of a Commission under my Hand and Seal, dated First Day of November 1643, directed to Mr Thomas Taylor, Citizen of London, he the said Thomas is authorized to raise a Company of Archers, for the service in Hand and to set the same on Foot, by and through the free Bounties of the well-affected People, in and about the City of London, and Parts adjacent, as by the Teneur of the said Commission appears”

It has been said that the last significant use of the longbow in a battle in Britain occurred at Tippermuir on 1st September 1644 when Montrose’s Royalist highlanders defeated an army of the Scottish covenanters commanded by Earl of Wemyss. The highlanders were still well known for their use of the longbow at this time and at Tippermuir the “Atholl and Banzenoch men had swords, bowes and fyrelockes”. In the Bishops Wars of 1639-40 longbow armed highlanders had played their part and from that conflict comes a wonderful description of the kind of men who fought at Tippermuir:

“They were all or the most part of them well timbred men, tall and active, apparelled in blew woollen wascotts and blew bonnets. A pair of bases of plad, and stockings of the same, and a paire of pumpes on their feet: a mantle of plad cast over the left shoulder, and under the right arm, a pocquet before their knapsack, armed a pair of durgs on either side of the pocquet. They are left to their owne election for the weapons; some carry onely a sword and targe, others musquetts and the greater part bow and arrows with a quiver to hould about 6 shafts maide of the maine of a goat or colt, with the hair hanging on and fastened by some belt or such like soe as it appears almost a taile to them”

Whilst Montrose and Wemyss were battling it out at Tippermuir, on the same day the Earl of Essex was losing the Battle of Lostwithiel in Cornwall. Whether Thomas Taylor’s company of archers took art in the battle is unknown but there can be little doubt that having been raised by Essex the previous November they almost certainly went on to join his army for the West Country campaign of 1644. However they were probably knocked out of the fighting in the West Country in mid-August for around 14th August 1644, Royalist troops plundered Lanhydrock House, the home of Parliamentarian Colonel Lord Robartes and “in the howes was found many bowes an divers of arrows” as noted in Richard Symonds Diary of the Marches of the Royal Army During the Great Civil War.

There is no evidence of Thomas Taylors company of archers after August of 1644 and it appears likely that if they had survived the long march out of Cornwall following the defeat at the Battle of Lostwithiel they were probably incorporated into another regiment and re-equipped with pikes or muskets or maybe even disbanded. Taylor himself continued in Parliaments service and ended his military career in 1647 when he was one of the three men who presented the Leveller tract “An Agreement of the People” to the army.

The use of the longbow did not entirely disappear with Taylors company as there is evidence of its use by Parliament at both the sieges of Colchester and Pembroke as well as the Royalists still having archers in the field in 1647 when James Winstone, a Parliamentarian soldier “was wounded in ye righte hande by an arrow” at a skirmish in Hathersage, Derbyshire but this is the last known acknowledgement of the longbows use.

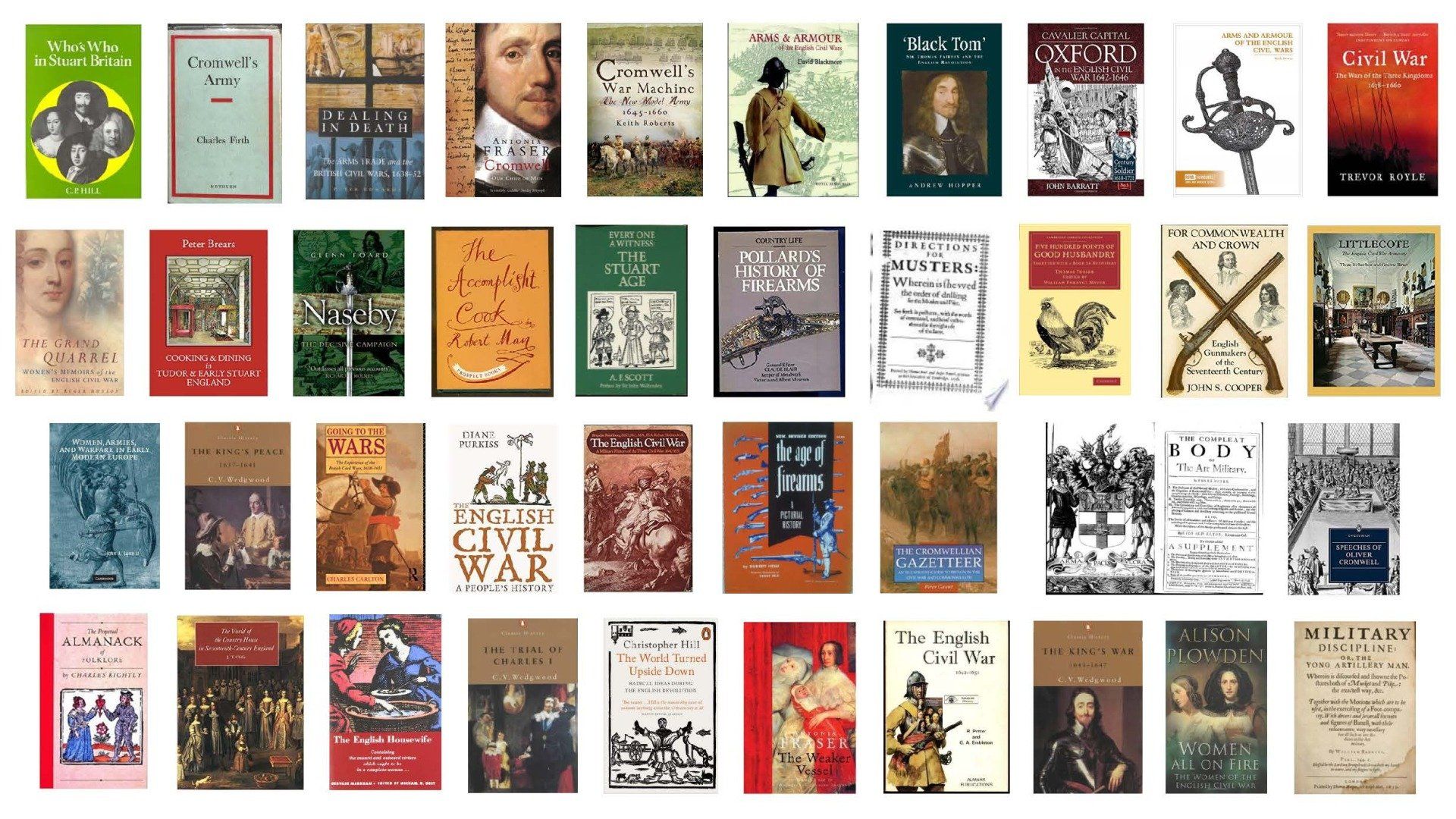

For reference I would strongly recommend you buy E T Fox’s book, Seventeenth Century Military Archery that contains the complete transcripts of William Neade’s The Double-Armed Man (1625),. Other worthwhile reading come in the form of the anonymous A New Invention of Shooting Fire-shafts in Long-Bows (1628) and Gervase Markham’s The Art of Archerie (1634) all available from Fox Historical Publications.