Doing It: Medieval Sex

You can leave your hat on...

- Virgins - not allowed to have sex

- Wives - allowed to have sex, with certain rules

- Widows - have had sex before, but not currently allowed to have sex.

- Whores - allowed to have sex, but socially excluded and vilified

- Virgins by circumstance - young, unmarried women, whose choices are marriage, if they can find a husband, or taking a vow of virginity

- Virgins by choice - this normally means nuns. It can also mean married or widowed women who have taken a formal vow of chastity before a bishop. Two famous examples of this are Margery Kempe (1373-1438 approx.), who negotiated a ‘chaste marriage’ with her husband after 14 children to devote her life to God, and Margaret Beaufort who took a vow of chastity in 1499 (with her husband’s permission).

Ask Nicely

You may also be having sex because your spouse asked nicely. Seriously.

The ‘marital debt’ is what the church refers to as the duty owed by each spouse to the other to have sex if it is requested to avoid falling into sin and seeking it elsewhere.

It comes about because of a Bible passage in 1 Corinthians:

“The husband should fulfil his marital duty to his wife, and likewise the wife to her husband. The wife does not have authority over her own body but yields it to her husband. In the same way, the husband does not have authority over his own body but yields it to his wife. Do not deprive each other except perhaps by mutual consent and for a time, so that you may devote yourselves to prayer. Then come together again so that Satan will not tempt you because of your lack of self-control.”

This marital debt is why a woman can only take a vow of chastity in marriage if both parties agree.

Chapter 3: The Equipment

I have a gentill coke...

A part, yard, member, cock, bow, lance, sword, pin, pillicock or cod, but not yet a penis!

Penis as a term is a 16th century one, but the word ‘bollocks’ has a very long pedigree - first used in c. 1000.

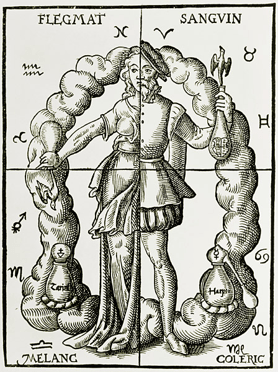

According to medical theory, semen is humour that has been refined into the male ‘seed’ necessary for procreation by the heat and dryness of the male body, the ‘cooking’ of which has turned it from red blood into white semen. Because it is therefore connected with the balance of humours, it is healthful to periodically release it in intercourse. However, if you orgasm too frequently the you run the serious risk of depleting your reserves of hot dry fluids making yourself sick, and potentially effeminate.

Also, it was thought that the hot air that men had in abundance was responsible for erections, so hold on to that, or your bellows may fail you.

All your quaint honour...

The most common non-slang word for the female part used in the medieval period is cunt. This was a descriptive term, albeit a bawdy one, but the truly offensive terms in the middle ages were blasphemous, not anatomical. Consider in modern life the changing levels of offensiveness of racial slurs.

The related term ‘quaynt’ (which also meant cunning, which potentially also shares a linguistic root) was also in use to mean the same thing - this pitches up in Chaucer and plays on the word quaynt, quaint and cunt appear regularly from Chaucer to Shakespeare and beyond.

Vulva as a term for the external female genitalia appears in the 14th century and vagina only starts being used in the 17th century.

Several medical writers (Galen and Avicenna among them) considered the female organs to be the same as the males but inverted. Hence, women also have testicles (ovaries to us) and produce ‘seed’ which is necessary for conception. This is why it was considered important that women experience orgasm for conception, to release their seed, and in the same way as men, regular emission of seed contributed to health.

Chapter 4: Doing it Right

When?

When: Can’t just have at this willy-nilly! You have to make sure it’s the right day for marital sexytimes. And not in daylight. For shame.

The church prohibited sex on Wednesday, Friday, Saturday, Sunday, during Lent and Advent, during Easter Week, during Whitsun Week, feast days, and when a woman in menstruating, pregnant or breastfeeding.

If none of those, then crack on.

Where?

Bed is usual! However, complete privacy was less common than now. Many poorer families slept multiples to the bed, and richer people would often have servants sleeping in in the room. Curtains around the bed help, but can only do so much! This is probably why people did need reminding not to shag on church grounds - and occasionally got dragged into court to punish them for it too.

“ 4 September, 1516 the lord bishop sitting in judgement in the chapel of his manor in Liddington ordered Amy Martynmasse of Sharnford in the county of Leicester, who was appearing before him in person and had confessed that she had been known carnally by Thomas Westmorland the curate of Uppingham within the rectory of Uppingham…”

How?

Positioning is very important. Some positions were thought to be too close to bestial or contraceptive in nature, which isn’t allowed, so missionary position is the only acceptable position to take for your shenanigans.

Chapter 5: Doing it Wrong

Wrong?

Here is one of the central problems for the Church. Since the fall from grace in the Garden of Eden, lust and sex have been intertwined. When Adam and Eve gained knowledge of good and evil, they also lost the state of innocence in which animals live, and sex becomes contaminated with lust. If humankind had not fallen from grace, sex would be as animals have it - purely for procreation. However, since humankind had a concept of good and evil now, and we make a distinction between moral and immoral acts, we require guidance as to what things will land us in hell.

SO, many of the church decrees around sexual activity and what is and is not acceptable aim to make sure that sex is as non-sinful as possible. This attempt to manage the sin of lust forms the basis of most prohibitions and rules around sex.

Sodomy!

ANY non-procreative sex. Regardless of who is doing it and to whom, if you can’t get pregnant from it, it’s sodomy. So yes, it covers man-on-man buttsex, but also heterosexual buttsex, oral, masturbation, dildos, bestiality, and exotic positions which might be contraceptive (cowgirl, standing).

While all these things are sodomy, there was a hierarchy of badness, and that hierarchy doesn’t necessarily treat homosexual acts as worse than heterosexual acts.

In Florence, for example, there was a court case for sodomy which ended in the man being burnt. But, he wasn’t just caught with another adult man, he ‘“with force and violence committed the act of sodomy” with a ten year old boy. The standard penance for the first offence of sodomy in Florence at the time was a 100 florin fine, and corporal punishments didn’t kick in until your 4th offence, and then you need two witnesses to it.

In other places we have evidence that some homosexual activities were on a par with solo joys:

12. If a woman practices vice with a woman, she shall do penance for three years.

13. If she practices solitary vice, she shall do penance for the same period.

From the Penitential of Theodore (7th century, reprinted up until the 12th)

Penitentials

Penitentials are interesting. The height of their popularity was between the 6th and 12th centuries (they were officially banned in the 12th century but this wasn’t well enforced across Christendom, many remained in existence and their advice crops up in a lot of other later writings).

A ‘penitential’ is a book that gives guidance to priests who are giving the Sacrament of Reconciliation, which was known as the Sacrament of Penance in the medieval period. You tell the priests your sins, he tells you the penance you need to perform to be reconciled to God.

One of the most influential was written by Burchard of Worms, a bishop in the Holy Roman city of Worms (Martin Luther also pitches up there 500 years later). He had a big influence on Canon law, but he also wrote his own penitential in C11th, which gives a shy priest questions to ask to winkle out confessions from reticent parishioners.

On paper, this is great - a list of common sins and what their punishments were. However, we have no way of knowing if the sins in the penitentials were what people WERE doing, or just what some bishops who spent a lot of time thinking it about it THOUGHT they were doing. Either way, we can gather an idea of what it was plausible to priests that their parishioners were up to.

Among the things Buchard thought were going on were:

Girl on girl dildo action: Have you done what certain women are accustomed to do, that is, to make some sort of device or implement in the shape of the male member, of the size to match your desire, and you have fastened it to the area of your genitals or those of another with some form of fastenings and you have fornicated with other women or others have done with a similar instrument or another sort with you? If you have done this you shall do penance for five years on legitimate holy days.

Or solo: Have you done what certain women are accustomed to do, that is, you have fornicated with yourself with the aforementioned device or some other device? If you have done this, you shall do penance for one year on legitimate holy days.

A woman swallowing semen is penalised with 7 years of fasting, and he prescribes ten days fasting for male masturbation, or married couples going at it doggy style.

Spells

The penitentials also describe potential magic spells for sex, all of which are no-nos. You can either inflame lust:

Have you done what some women are wont to do? They take a live fish and put it in their vagina, keeping it there for a while until it is dead. Then they cook or roast it and give it to their husbands to eat, doing this in order to make the men be more ardent in their love for them. If you have, you should do two years of penance on the appointed fast days’

Or bring harm:

“Hast thou done what some women are wont to do? They take off their clothes and anoint their whole naked body with honey, and laying down their honey-smeared upon wheat on some linen on the earth, roll to and for often, then carefully gather all the grains of wheat which stick to the moist body, place it in a mill, and make the mill go round backwards against the sun and so grind it to flour; and they make bread from that flour and then give it to their husbands to eat, that on eating the bread they may become feeble and pine away. If thou hast [done this], thou shalt do penance for forty days on bread and water."

It seems odd to us that magic vagina fish magic carries a less harsh penalty from a bishop than two ladies with a marital aid or a wifely blowjob, but here is where the procreative factor comes into it again.

The wife meddling with a perch is seeking more of an acceptable form of sex from her husband. She’s going about it a bad way, and is probably driven by lust, but nevertheless. Dildos and blowjobs are explicitly non-procreative and solely pleasurable - therefore doing it a much worse sin.

Impotence

What if you can’t do it at all? Well, according to the logic of the medieval Church - no sex, no babies, no point. Inability to raise the staff is a legitimate reason for having a marriage annulled, but there was a process to determine whether this really was a big problem.

This was one of the ‘lawful impediments’ that are asked for in a marriage ceremony - if someone knows that the groom’s bits are purely decorative, they need to speak up.

But if not, then after 3 years, the wife can apply for an annulment, and if granted, both parties can remarry. Even if nobody denies it, there needs to be ‘Congress’ to prove that the husband is impotent.

Thomas Chobham (1160 - 1230) lays out the procedure:

After food and drink the man and woman are to be placed together in one bed and wise women are to be summoned around the bed for many nights. And if the man’s member is always found useless as if dead, the couple are well able to be separated.

And this seems to be exactly what happened. In 1370 for poor John Sanderson in York:

Congress was performed and the matrons reported the following back to the court; the member of the said John is like an empty intestine of mottled skin and it does not have any flesh in it, nor veins in the skin, and the middle of its front is totally black. And said witness stroked it with her hands and put it in semen and having thus been stroked and put in that place it neither expanded nor grew. Asked if he has a scrotum with testicles she says that he has the skin of a scrotum, but the testicles do not hang in the scrotum but are connected with the skin as is the case among young infants.

And in 1433 (again for a John in York), things were very thoroughly tested!

"exposed her naked breasts and with her hands warmed at the said fire, she held and rubbed the penis and testicles of the said John. And she embraced and frequently kissed the said John, and stirred him up in so far as she could to show his virility and potency, admonishing him for shame that he should then and there prove and render himself a man. And she says, examined and diligently questioned, that the whole time aforesaid, the said penis was scarcely three inches long".

Further Reading...

Primary:

- Thomas Aquinas, Summa Theologiae

- Various, Patrologia Latina

- St. Augustine, Confessions

Secondary and Translations:

- Kate Lister, A Curious History of Sex

- Ibid, The Bishop’s profitable sex workers, wellcomecollection.org

- Henrietta Leyser, Medieval Women

- Ian Mortimer:The Time Travellers Guide to Medieval England

- Ruth Mazo Karras,Sexuality in Medieval Europe

- Rosalie Gilbert,The Very Secret Sex Lives of Medieval Women

- Beryl Rowland, Medieval Woman’s Guide to Health

- Eleanor Janega, Various articles, Going-medieval.com

- P. J. P. Goldberg, Women in England 1275 - 1545

- G. Brucker, The Society of Renaissance Florence. A Documentary Study

- John T. McNeill and Helena M Gamer,

Medieval Handbooks of Penance.