Standards of the English Civil War

[Note: This series of articles was written by Charles Kightly, illustrated by Anthony Barton and first published in Military Modelling Magazine. The series is reproduced here with the kind permission of Charles Kightly and Anthony Barton. Typographical errors have been corrected and comments on the original articles are shown in bold within square brackets.]

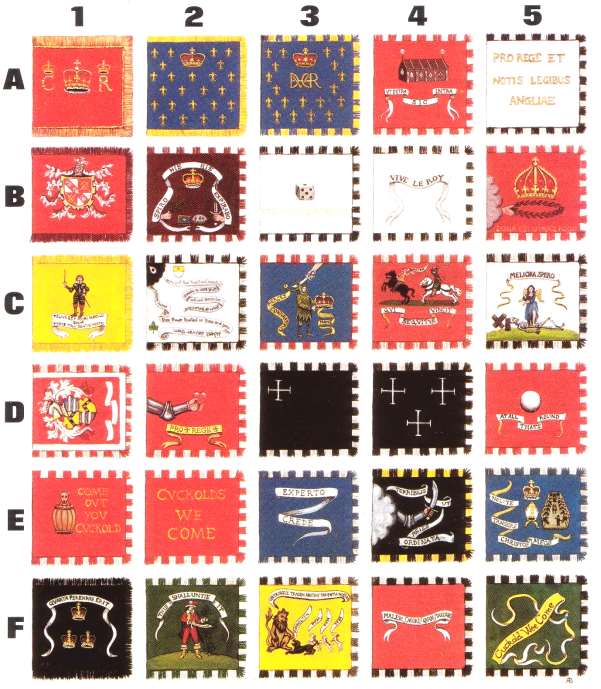

The Parliamentary Infantry

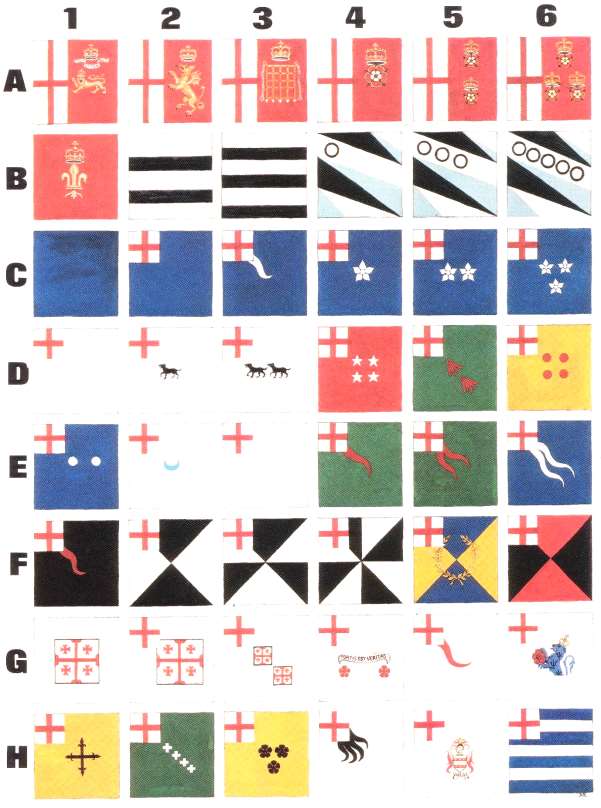

During the Civil Was, there were no regimental colours as such, each company of an infantry having its own. A full strength regiment, therefore, might have as many as ten, one for each of the colonel's company, first, second, third captain's company etc. All the standards of the regiment were of the same basic colour (B1), sometimes with a motto (A1). All the rest, however, had in their top left corner a canton with the cross of St. George in red on white; lieutenant-colonel's colours bore this canton and no other device.

In the system most commonly followed by both sides (pattern 1) the major's colour had a 'flame' or 'stream blazant' emerging from the bottom right hand corner of the St. George (A3), while the first captain's company bore one device, the second captain's two devices, and so on for as many colours as there were companies. Variant styles, however, were in vogue amongst the London militia or Trained Bands, and possibly elsewhere. One of these (pattern 2) continued the use of the major's flame, the first captain's colour bearing two of these, the second captain's three etc., arranged round the canton. In the other (pattern 3) the major's colour bore a single device rather than a flame, the first captain's two devices, and so on.

The devices used by parliamentary infantry seem usually to have been conventional ones, such as stars, balls, lozenge-shapes etc. rather than devices taken from the heraldic arms of the colonel, though Lord Saye's regimental colours did employ his family's rampant lions. Even so, standards rarely broke the heraldic rules by placing metal (gold and silver and hence yellow and white) on metal or a colour (red, blue, green etc.) on a colour; thus, one would not normally expect to find, say, yellow devices on a white standard or blue devices on a red one. Nor were a regiment's colours always the same hue as its coats. Early in Charles I's reign, foot colours were described as being seven and a half feet long (next to the pole) by nine feet long (in the fly) but by the time of the Civil War they had been reduced to a rather more moderate size of six and a half feet square, the canton of St. George being between one and a half and two feet square. In order to fly gracefully, and to be manageable in a wind, they were made from two thicknesses of some lightweight material, like silk or taffeta, the devices being painted rather than embroidered. Standard poles seem generally to have been rather short (perhaps about eight to ten feet long) both for ease of management and to facilitate the ceremonial flourishing of colours so much recommended by seventeenth-century military writers. Contemporary illustrations show the poles to have been topped by a spearhead, but more decorative devices may also have been used. One such, perhaps, was the brass dove, fitted with a socket for a staff, found in a ditch near the battlefield of Cropredy Bridge, Oxon.

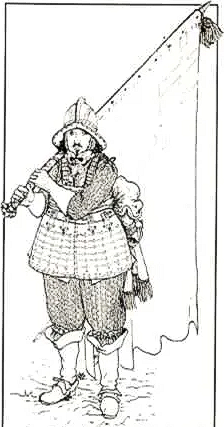

Colours were carried by the ensign, who was the company's most junior officer, ranking below the captain and his lieutenant. He was not always a young man, though, since the colours would be a focus of enemy attacks, he needed to be both courageous and agile. In some cases, at least, he would be provided with a guard of men armed with handy pole-weapons like halberds. Many rules were laid down by military authorities for the ensign's conduct on ceremonial occasions, though how much these were observed in the field is another matter. At no time, for instance, was he to carry the standard-pole with more than one hand “but if the wind blow stiff... then he may set the butt against his waste and not otherwise”. He was to dip and flourish his colours to honour the general 'or any Noble Stranger', and on no account was he to lay them on the ground when the company halted but rather furl them and prop them up with sergeants' halberds. As an officer, the ensign would not have worn uniform but his own civilian clothes.

The hazards of his office would also call for defensive armour, most probably a pikeman's suit with or without extra decoration (see illustration).

The ceremonious treatment of the colours was not merely Baroque nonsense, for in some ways they were (like Roman eagles) the heart and soul of the company and regiment. On the march they were carried at the head of the company's pikes (supposedly a more honourable weapon than the musket) or massed together with the collected pikes of the regiment. In battle, of course, their main use was an easily identifiable rallying point, so here, too, they were placed with the stand of massed pikes which was the regiment's chief strength and stay. Even if the pike-stand broke, the colours provided a centre for last-ditch resistance, as at Naseby when the front line of parliamentary foot were forced back in disorder. "But the Colonels and Officers, doing the duty of very gallant Men, in endeavouring to keep their men from disorder, and finding their attempt fruitless therein, fell into the Reserves with their Colours, choosing rather there to fight and die than to quit the ground they stood on." (Joshua Sprigge: Anglia Rediviva).

A regiment that lost all its colours therefore (as several royalist regiments did at the same battle of Naseby) was an utterly broken and routed unit, and one that “cast its standards away in flight" was likely to be little better. Captured colours were a solid proof of success, the more the colours the greater the victory. Contemporary accounts of actions, therefore, nearly always include some such phrase as (in this case referring to the capture of Wakefield, May 20th 1643) “We took all their Officers prisoners, 27 Colours of Foot, 3 Coronets (i.e. standards) of Horse and about 1500 Common Souldiers..."

Colours taken by the Parliamentary army were often sent to be presented to the House of Commons – that is, when they could be found, for the soldiers who captured them sometimes preferred to tear them up for trophies. Partly to prevent this, substantial rewards were given when they were handed over, and the account books of the New Model Army contain such items as:

- “For colours taken at Langport fight (10th July, 1645) by the General's order - £7”

- "To Monsieur Pridagh the Frenchman for taking colours from the enemy upon a single encounter - £5."

- “To Lieutenant Knight who tooke the black colours att the storming of Bridgewater (21st July, 1645)-£10."

Several instances are known of Parliamentary ensigns capturing colours from their enemy counterparts, and Ensign Young of Sir William Constable's bluecoats was responsible for taking the royal standard at the battle of Edgehill, 1642. At the storm of Bridgewater, 1645, the ensigns of the Lord General's regiment were also in the fore, planting their colours on the royalist fortifications to encourage their comrades. Colours could also be used to deceive, as when Colonel Hutchinson, parliamentary governor of Nottingham, being desperately short of men, displayed far more colours on his defences than he had companies in the town; the enemy were taken in, and delayed their assault long enough for Hutchinson to send for reinforcements. On occasion the deception was unintentional, and several unfortunates were taken prisoner after mistaking the similar colours of an enemy regiment for their own.

The discussion will be continued later in an article on Royalist infantry colours. Appended here, however, is a list of all Parliamentary foot standards known to the authors, including brief notes on the service of the regiments concerned.

[Note: This isn’t complete – more colours have come to light since the article was written – notably the whole set for Nicholas Devereux’s Regt, depicted in a contemporary painting of Malmesbury].

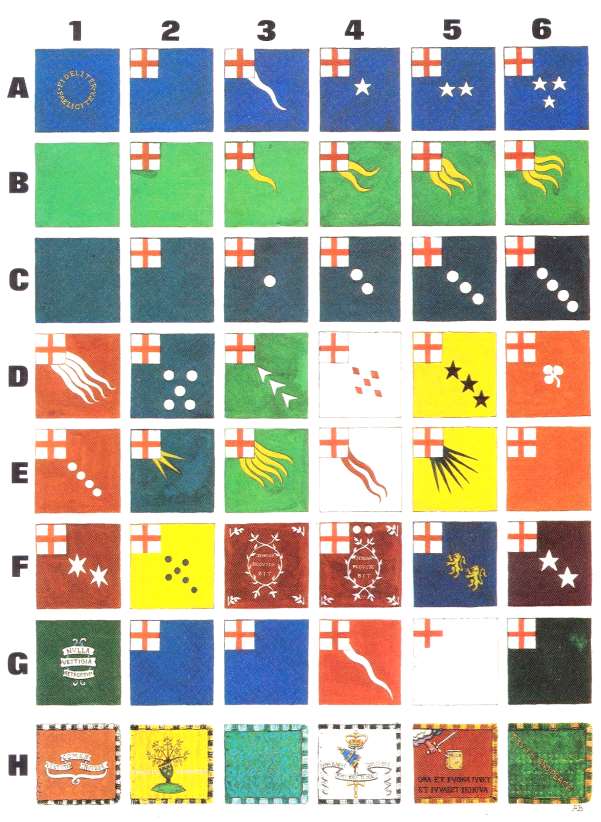

Key to illustrations of Parliamentary foot colours

r = raised; disb.= disbanded; m = merged; s served; n.d.k.= colour of standard but no devices known.

Lines A, B, and C illustrate the three types of differencing in use with the Parliamentary army. Letters in round brackets indicate system used by regiment. All regiments of the London Trained Bands probably served at Turnham Green, 1642. Numbers in square brackets indicate number of companies, where known.

A. 1-16 Charles Fairfax's Regiment New Model Army

r. West Yorkshire, 1648

s. Pontefract Castle, 1648, Dunbar, 1650, Worcester, 1651 [10] Motto on Colonel's colour means 'Faithfully and Fortunately'

LONDON TRAINED BANDS

B. 1-16 Green Auxiliaries

s. with Waller's Army, Autumn, 1643, including battle of Alton, Hants. December, 1643. [7]

C. 1-6 Blue Regiment

s. Relief of Gloucester, Aldbourne, First Newbury, 1643 [7]

D.1 Red Regiment (as B) 3rd Captain's Co.

s. as Blue Regt. [7]

D.2 Blue Regiment 4th Captain's Co.

D.3 Green Regiment (as C) 2nd Captain's Cs. as Blue Regt. [6]

D.4 White Regiment (as C) 4th Captain

s. Cheriton, March, 1644. [7]

D.5 Yellow Regiment (as C) 2nd Captain

s. Cheriton, March, 1644. [7]

D.6 Orange Regiment (as C) Major. [6]

E.1 Red Auxiliaries (as C) 2nd Captain.

s. Relief of Gloucester, Aldbourne, First Newbury, 1643. [7]

E.2 Blue Auxiliaries (as B) 2nd Captain.

s. as Red Auxiliaries. [7]

E.3 Green Auxiliaries 4th Captain.

s. with Waller's Army, Autumn 1643, including battle of Alton, Hants. December, 1643.

E.4White Auxiliaries (as B) 1st Captain. [7]

E.5 Yellow Auxiliaries (as B) 4th Captain.

s. as Green Auxiliaries [8]

E.6 Orange Auxiliaries (n.d.k.) Lieutenantcolonel.

s. as Red Auxiliaries.

F.1 Westminster Regiment (as C) 1st

Captain.

s. as Green Auxiliaries [7]

F.2 Southwark Regiment (as A) 6th

Captain.

s. Cropredy Bridge campaign, 1644 [9]

F.3 & F.4 Tower Hamlets Regiment Colonel and 1st Captain.

s. as Southwark Regiment [7]

Motto means 'Jehova [God] will provide'.

ESSEX'S ARMY

F.5 Lord Saye and Sale's Regiment, later

Meldrum's, later Aldrich's (as A) 2nd Captain

r. Oxfordshire.

s. Edgehill 1642, 1st Newbury, 1643,

Lostwithiel, 2nd Newbury 1644. m. New Model Army, 1645 as Lloyd's. Retained these colours until at least 1644. [10]

F.6 Lord Brooke's Regiment (as A) 2nd

Captain. This was the company colour of Captain John Lilburne, the Leveller.

r. London

s. Southam, Edgehill, Brentford 1642, disb. 1643. [10]

G.1 John Hampden's Regiment (n.d.k.) later Tyrrel's, later Ingoldsby's, Colonel.

r. Buckinghamshire

s. Southam, Edgehill, Brentford, 1642, 1st Newbury, 1643? Lostwithiel, ? Second Newbury, 1644.

m. New Model, 1645.

Motto means 'Not one step backwards' (We never retreat).

[Note: Currently it is thought that this design was instead Hampden’s cavalry cornet].

WALLER'S ARMY

G.2 Sir William Waller's Regiment (n.d.k.) Lieutenant-Colonel.

s. Waller's Campaigns September, 1743-5, including Alton 1643, Cheriton and Cropredy Bridge 1644.

m. New Model, 1645 [10]

G.3 Herbert Morley's Regiment (n.d.k.) Lieutenant Colonel.

r. Sussex.

s. Siege of Arundel Castle, 1643, Basing House, 1644 [5]

G.4 Colonel Richard Onslowe's Regiment (n. d. k.) Major.

r. Surrey.

s. Basing House, 1644 [6]

G.5 Colonel Samuel Jones' Regiment (n.d.k.) Lieutenant-Colonel.

r. Surrey.

s. Garrison of Farnham, 1643-5. Basing House, 1643-4, Cheriton, 1644.

NEW MODEL ARMY

G.6 Colonel Thomas Rainsborowe's

Regiment (n.d.k.) Lieutenant-Colonel.

s. Naseby, Bridgewater, Bristol, 1645.

[Note: the hue is 'sea green' -- adopted as a party colour by the Levellers and their sympathisers, especially after Rainsborowe's murder in 1648, and probably relates to the Tower Guard Rgt commanded by Rainsborowe at his death].

GENERALS' PERSONAL STANDARDS

These were carried to mark the position of a general on the field, and borne by his personal lifeguard of horse. They were about 2 feet square, the same size as cavalry standards.

[Note: Much confusion has arisen over ‘personal standards’, these were simply the cornet of the general’s lifeguard troop. Sometimes lifeguard troops deployed independently, but often formed the first troop of the general’s own regiment of horse]

H.1 Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex.

Commander of the main Parliamentary Army, 1642-5. Commander-in-chief at Edgehill, 1642, First Newbury, 1643, Lostwithiel and Second Newbury, 1644.

Motto means: 'Virtue attracts envy'

H.2 Sir William Waller

Command of various armies, especially in southern England, 1642-5. Commander-in-chief at Lansdown, Roundway Down, Alton, 1643, Cheriton and Cropredy Bridge, 1644.

Motto means:' The fruit of virtue'

H.3 Sir Thomas Fairfax

Commander-in-chief, New Model Army, 1649.

Commanded at Naseby, Langport, Bridgewater, Bristol, 1645, Torrington, 1646, Maidstone, Colchester, 1648.

The hue is 'peacock blue'.

H.4 Ferdinando Lord Fairfax (father of the above)

Commander of Northern Parliamentary Army, 1642-5. Commanded in Yorkshire campaigns and present at Marston Moor, 1644.

The Spanish motto translates as 'Long live the King and Death to Bad Government'

H.5 Major-General Philip Skippon

Commander of infantry in Essex's army and in New Model Army. Present at 1st and 2nd Newbury, in most of Essex's campaigns, and at Naseby.

Motto means: 'Pray and fight. Jehova helps and will help you'.

H.6 Edward, Earl of Manchester

Commander, Eastern Association, 1643-5.

Commanded at Winceby, 1643 and Lincoln, 1644, present at Marston Moor and 2nd Newbury, 1644.

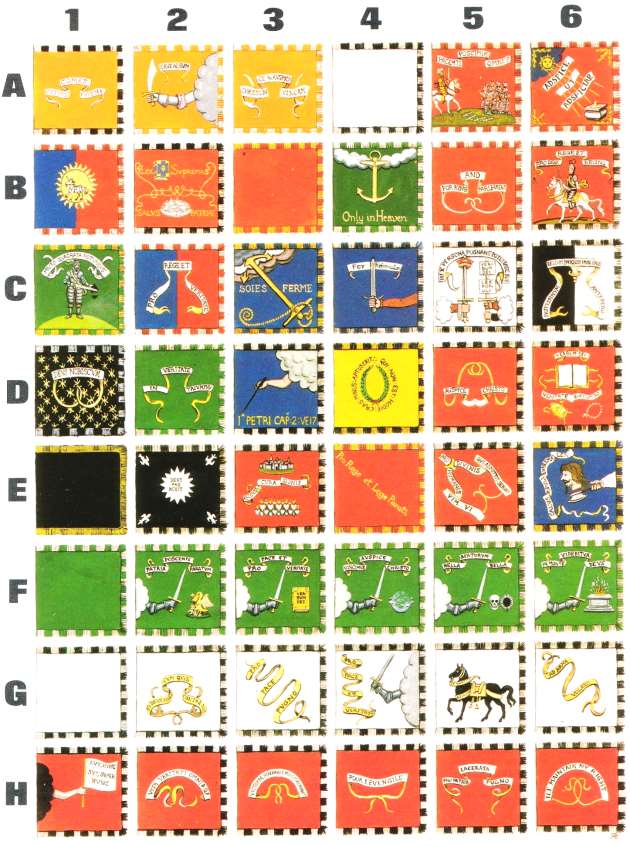

The Royalist Infantry

A considerable number of Royalist infantry colours are known, the principal sources of information being, ironically, the records of their Parliamentarian opponents who captured them with increasing regularity as the war turned against the King. Many of these captured standards were sent as trophies of victory to the House of Commons, where some unidentified artists (to whom military historians must be forever grateful) carefully drew and painted them in volumes which still survive in various archive collections.

As might be expected in a civil war, the military systems used by both sides were similar. In the Royalist, as in the Parliamentary army, regiments of foot were composed of companies, nominally of about a hundred men each, and each of these had its own colour. Up to ten standards, therefore, might be carried by a full strength regiment, one each for the colonel's, lieutenant-colonel's, major's, first, second, third and fourth captain's companies, etc. This was the ideal but (especially towards the end of the war) Royalist regiments were rarely up to strength and by the battle of Naseby in 1645 some were down to two or three companies, having to be 'brigaded' together to form one unit of regimental size.

Standards were made of painted silk or taffeta, and were six and a half feet square. Within a regiment all were of the same basic colour, but several methods were used to distinguish the different companies, the most common system being apparently that shown in Cl-6. Here the colonel's colour is plain, but all the rest have cantons of St. George (between eighteen inches and two feet square) in the top left hand corner. The major's colour is further differenced by a streamer issuing from the canton, the First Captain's has one device, the Second Captain's two, and so on. Another common system (see E4-5) had the same type of Colonel's Lieutenant-Colonel's and Major's colours as above - indeed, these were almost universal - but dispensed with devices, the First Captain having two streamers from the St. George, the Second Captain three, etc.

The systems above were used by both sides indiscriminately (see the Parliamentary infantry colours in June Military Modelling), Colonel Cooke's Royalist regiment (E1), for instance, bearing exactly the same colours as those carried by the Blue Regiment of the London Trained Bands on the opposing side. This situation undoubtedly gave rise to considerable confusion on the battlefield, and many examples are known where soldiers mistook an enemy regiment with similar colours for their own, with disastrous results. Perhaps for this reason, some Royalist regiments adopted a system which, as far as we can tell, was confined to the King's army. In this (F2-6) the field officers' standards were conventional, but the

Captains' were distinguished by an increasing number of geometrical segments (or ‘gyrons’) in contrasting colours. One regiment with this type of colour, Gerrard's (F5) further decorated them with gold wreaths, perhaps a battle honour granted for some notable action.

Where conventional devices were used, these were often derived from the colonel's coat of arms. Stradling's cinquefoils, Talbot's hounds, Astley's hawk-lures and Percy's crescents all fall into this category, and Sir Henry Bard's 'cross potent' appears even on the normally plain colonel's colour of his regiment (G1-3). One commander, a certain Martin from Yorkshire, even displayed his whole arms crest, mantling, motto and all - on his colour (H5), which was considered 'bad form' by contemporary heralds. A few royalist units (none, unfortunately, identified) clung to a rather old fashioned design of contrasting stripes reminiscent of the standards of Queen Elizabeth's day (H6).

The colours of the King's Lifeguard of Foot, as befitted its special status, were quite different from those of any other regiment, for the St. George's cross extended the whole length of the hoist. Colonel's, Lieutenant-Colonel's and Major's standards all displayed one of the royal badges, and those of the Captains were differenced with crowned English roses. The colours of Prince Rupert's regiment, by contrast, were very un-English indeed. Like their colonel, these were German in style, and employed the black and white livery colours of the Rhineland Palatinate from which Rupert hailed. The Queen, too, used her national device, the French fleur-de-lys, on both the colours of her foot regiment and the standards of her troop of horse.

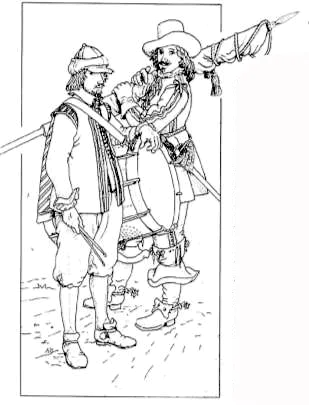

The colours were carried by an ensign, the most junior officer of the company, who (when there was any money to be had) was paid a guinea a week, considerably more than a private soldier with his weekly four shillings but less than his captain who received a weekly £2.12/6d. Like all other officers he provided his own clothes rather than wearing the regimental uniform coat. Ensigns were usually 'gentlemen', like the Welshman John Gwyn who, after a short spell in the ranks, was promoted to carry a colour in the regiment of his fellow-countryman Sir Thomas Salisbury. In his memoirs he tells us how 'for my further encouragement I had the colours confirmed on me, to go on as I began'. His post naturally made him the focus of enemy attention, and when Gwyn's unit was forced to retreat during the first battle of Newbury (1643), it was his skill at vaulting with the standard pole that saved him... 'with the colours in my hand, I jumped over hedge and ditch, or I had died by multitude of hands'. In such circumstances agility was the best protection, but many ensigns probably wore some armour, if only the gorget, the usual mark of an officer.

A1-6 King's Lifeguard (Red Coats) Colonel's. Lt-Col's, Major's. 1st, 2nd and 3rd Captains'.

r. Lincs., Derbs. and Cheshire. Originally 12 companies.

s. Edgehill, 1642. First Newbury, 1643. Cropredy Bridge/Western Campaign/2nd Newbury, 1644. Virtually destroyed at Naseby, 1645, where all these six colours were captured.

B1. Queen's Regiment (Red Coats)

Colonel's colour - other colours unknown. Little is known of the service of this regiment, though it certainly fought at Cropredy Bridge. This colour was captured by the Parliamentary army of the Earl of Essex at some unknown place. See also Sir Henry Bard's Regt. below.

B2-6 Prince Rupert's Regiment (Blue Coats)

Col. Lt. Col., 1 st, 3rd and 5th Captain

r. Somerset, as Sir Thomas Lunsford's Regiment. Taken over by Rupert, 1643.

s. Edgehill, 1642. In the west, including Lansdown and the Siege of Bristol, and at Chalgrove, 1643. Marston Moor, 1644. Virtually destroyed at Naseby, 1645, where seven colours were lost. These unusual colours, which are of German type, may only have come in when Prince Rupert took over the regiment.

[Note: The black and white stripy flags B2 and B3 are now thought to belong to another regiment, not Prince Rupert’s]

C1-6 Sir Edward Stradling's (later John Stradling's) Col., Lt. Col., Major, 1st, 2nd, 4th Captain.

r. S. Wales.

s. Edgehill, 1642. ? 1st Newbury, 1643. Cropredy Bridge, 2nd Newbury, 1644. ? Naseby, 1645.

D1-3 Sir Gilbert Talbot's (Yellow Coats) Lt. Col., Major, 1st Captain.

r. ? Shropshire. s. Cheriton, Cropredy Bridge, 1644. The dogs on these colours are 'talbot-hounds', badge of the colonel's family.

D4 Lord Hopton's (Blue Coats) 3rd Captain (system as Talbot's)

r. West Country.

s. Western campaigns including Lansdown and Bristol, 1643. Cheriton and Cropredy Bridge, 1644. Western campaigns, 1645-6.

D5 Sir Bernard Astley's (formerly Marquis of Hertford's) 1st Captain (system as Talbot's).

s. Western campaigns including Lansdown and Siege of Bristol. Cheriton (?), Cropredy, 2nd Newbury, 1644. Naseby, 1645. The devices are hawk’s lures.

D6 Sir Lewis Dyve's 3rd Captain (system as Talbots).

r. Lincs. and Beds.

s. Edgehill, 1642. Garrison of Abingdon, Cheriton (~), Cropredy, 1644. Garrison of Sherborne Castle, Dorset, 1645.

E1 Col. Cooks's 1st Captain (system as Talbot's).

s. Cropredy Bridge, 1644.

E2 Henry Lord Percy's (White Coats)

(system as Talbot's).

Recruited from the Yorkshire regiments, this unit escorted the Train of Artillery (of which Percy was commander) at Cheriton and (?) Cropredy Bridge, 1644.

E3 Sir Richard Bolle's (later Sir George

Lisle's) Lt. Cot's. (system as Talbot's).

r. Staffs.

s. Edgehill, 1642. First Newbury, 1643. Bolle was killed at Alton, Dec. 1649. Under Lisle the unit served at Cheriton, Cropredy and 2nd Newbury 1644. Naseby, 1645.

E4-5 Sir William Pennyman's (later Sir James Pennyman’s, later Richard Page's) Major and 1st Captain.

One of the first royalist regiments, raised from the Yorkshire Trained Bands.

s. Edgehill, 1642. Cropredy, 1644. Naseby, 1645, where several of their colours were taken.

E6 Anthony Thelwall's (formerly Sir Edward Fitton's) 1st Capt. - (system as Pennyman's).

r. Cheshire.

s. Edgehill, 1642. Siege of Bristol, First Newbury, 1643. Cropredy, 2nd Newbury, 1644.

F1-4 Sir Allen Apsley's (Red Coats) Major. 1 st, 2nd and 3rd Captain's.

s. Cropredy Bridge, 1644. ? West Country

1645-6.

F5 Charles Gerrard's (Blue Coats) 1st

Captain's - (system as Apsley's).

r. Lancs., Ches. and N. Wales.

s. Edgehill 1642. Lichfield, Bristol and First Newbury, 1643. Relief of Newark, Cheriton, S. Wales, 1644. ? Wales, 1645, Garrison of Oxford.

F6 Duke of York's 1 st Captain's - (system as Apsley's).

s. Garrison of Mariborough, 1644. Newbury 1645 where six of its colours were taken.

G1-3 Sir Henry Bard's (Grey Coats)

Colonel, Lt. Col., 2nd Captain.

The history of this unit, and of its commander, is a remarkable one. It was originally raised in spring 1644 from Yorkshire soldiers sent to Oxford with a

convoy. Shortly afterwards, however, it was virtually wiped out at the battle of Cheriton, where Sir Arthur Haslerig's “Lobsters” ‘killed or took every man’. Bard himself was then taken prisoner, having lost an arm. Released in 1645, Bard raised a new regiment with similar colours to the old one: it may have been recruited from members of the Queen's Redcoats (see above B 1) and was itself sometimes known as the Queen's Regiment. The new unit was no more fortunate than the old one for, after a spell as the garrison of Chipping Camden, it was decimated at Naseby, where the colours shown were taken. After the war Bard went into exile, and after various adventures was sent to the Shah of Persia in 1650 to raise money for the Royalist cause. He eventually died of heatstroke in India in 1656.

G4-6 City of Oxford Regiment. Lt. Colonel, Major, 1st Captain.

r. Oxford December, 1643 from townsmen rather than students. Given to Col. William Legge, governor of Oxford, 1645. A garrison regiment, it probably took no part in field campaigns.

F1 John Lamplugh's Regiment (White or

Grey Coats) 1st Captain.

r. Yorks. and Cumberland.

s. Northern campaigns and Marston Moor, 1644 where it was wiped out. This is the only one of the Marquis of Newcastle's famous White Coat regiments whose colours are certainly known.

H2 Unknown 4th Captain, H3 Unknown 3rd Captain, H4 Unknown 4th Captain.

These three colours were taken at Marston Moor: some or all of them may have been those of White Coat regiments

F5 Unknown Lt. Colonel's colour. Taken by Essex's army.

The arms are those of the family of Martin from Yorkshire.

F6 Unknown of old-fashioned type. taken as above.

Some other unidentified Royalist colours taken by the Parliamentary forces...

Taken at Edgehill. 1642.

A blue colour with St. George's cross and one white hawk's lure (as on Sir Bernard Astley's colours). Two red colours with St. George's cross and devices of white balls (as on Sir Lewis Dyve's colours) - perhaps belonged to Lord General's Regiment.

Taken at Marston Moor, 1644.

Eleven red colours, six yellow, four white, three green and one blue colour.

Taken at Naseby, 1645.

Four blue colours (a Lt. Colonel's and '1st, 3rd and 4th Captains') the last three having white stars like those on Hopton's colours. As well as near one hundred other colours both of horse and foot'.

Uniforms of some regiments whose

colours are unknown...

Sir Ralph Dutton's -White Coats.

r. Gloucestershire.

s. Edgehill, 1642. Siege of Bristol, 1643. Greenland House, 1644 ? Naseby, 1645.

Sir John Paulet's - Yellow Coats.

r. Late 1643 from troops returned from

Ireland.

s. Cheriton, 1644, Winchester, 1645.

Sir Matthew Appleyard's - Yellow Coats.

r. as above, Paulet's.

s. Cheriton, Cropredy, Western Campaigns, 1644. Naseby, 1645.

Sir Henry Tillier's and Robert Broughton's Both Green Coats.

r. 1644 from troops from Ireland.

s. Relief of Newark, 1644. Badly cut up at

Marston Moor, survivors fought at Montgomery, 1644, and (as 'the Shrewsbury Foot') at Naseby, 1645.

[Note: Although clear evidence exists that Tillier’s had green coats, the evidence for Broughton’s is unclear].

The Parliamentary Cavalry

During the summer of 1642, both the King and his Parliamentary opponents were busy recruiting a force of cavalry for the coming struggle; but the methods they respectively employed were, at first, somewhat different. While the King, from the outset, raised regiments of horse with a nominal strength of 500, the Parliamentarians began by organising their cavalry into individual troops. These were each commanded by a captain, assisted by a lieutenant, a cornet (who carried the standard) and a quartermaster, and included three corporals, two trumpeters, and a number of troops ranging from the statutory minimum of forty to an ideal sixty. Each captain was allowed £1,100 "mounting money" to provide horses and arms for his men of which the captain himself received £140 and the cornet about £50, while around £15 was considered adequate for the mount and equipment of a trooper. By the outbreak of large-scale hostilities in September, 1642, about 80 troops had been raised in this way, including the heavily armoured Lifeguard of the Commander-in-Chief, the Earl of Essex (recruited from the young gentlemen and lawyers of the Inns of Court) and the 67th troop raised in Huntingdon by Captain Oliver Cromwell.

The system of independent troops proved to be far from effective in the field, and at the first major battle of the war, Edgehill (October 23rd 1642), these small units were grouped into ad hoc 'regiments' composed of about six troops each. Though Essex's (A1-3) and Balfour's (A5-B2) regiments did well in this battle, the remainder of the Parliamentary horse were no match for the Royalist cavalry, and were speedily driven from the field. The overall quality of Parliamentary cavalry during the early part of the war, indeed, was not good and Cromwell remarked to John Hampden that, "Your troops ... are most of them old, decayed serving men and tapsters and such kind of fellows, and ... their troopers are gentlemen's sons, younger sons and persons of quality: do you think that the spirits of such base and mean fellows will be ever able to encounter gentlemen that have honour and courage and resolution in them? ... You must get men of a spirit ... that is likely to go on as far as gentlemen will go or ... you will be beaten still ... I did do so ... I raised such men as had the fear of God before them, and made some conscience of what they did, and from that day forward ... they were never beaten".

One of the first steps towards the improvement of the Parliament horse was the decision to organise them into permanent regiments. Cromwell himself had a commission to do so by the end of 1642, and his single troop had grown to a regiment of five troops by March, 1643,and of ten troops by the following September, eventually reaching a strength of fourteen troops or nearly a thousand men. This, however, was an exceptionally large unit, and in 1643-4 Parliamentary horse regiments more usually contained five or six troops of about 70 men each. When the New Model Army was established in 1645, six troops became the standard number (see F, G and H) but these each contained about 100 officers and men, giving a regimental strength of 600. After 1648, however, the number in a troop was reduced to 80.

From the beginning, each troop on both sides had its own standard which was made of silk, taffeta or a similar material and was invariably fringed, often in strips of two contrasting colours. It was about two feet square and was carried on a pole or a specially adapted lance by the cornet of the troop, a junior officer whose rank roughly corresponds to that of a modern second-lieutenant. In 1648 he received pay of 4/6d a day, half as much again as the daily wage paid to an ensign of foot: out of this, however, he had to provide for his horse as well as himself. As an officer, the cornet would have worn his own clothes rather than any kind of uniform but, like other cavalrymen, he would doubtless have worn a buffcoat, pothelmet and back-and-breastplate. The standards themselves, incidentally, were frequently called "cornets".

In the days of independent troops, the basic colour of the standard depended on the preference of the captain and, when troops were first amalgamated together, standards of different hues will have appeared within the same "regiment". This must have made for confusion, and when permanent regiments came in it is virtually certain that all their troop cornets were made the same colour, as in the case of Essex's regiment (A1-3).

Certainly this was the rule in the New Model Army, where Horton's regiment (F1-6), if not others, also had a standardised primary device, with an individual motto and secondary device for each troop. It also seems likely that regiments kept the same colour of standard and fringes when their commanding officers changed: thus Heselrige's regiment (B4) kept its green cornets and green and white fringes when it became Horton's (F16), and Livesey's (B5) passed on its red cornets and black and white fringes to its offshoots, Ireton's (D5) and Skinner's (H1-6).

Some standards, especially those of generals (A4, E1) or colonels (B3, F1, G1), were of plain damask silk, but the vast majority had a motto painted on them, accompanied in many cases by a device: mottoes frequently appeared without devices but not, apparently, vice-versa. The devices used by both sides were often copied from the woodcuts in books of "Emblems”- symbolic representations of vices, virtues, and qualities- which had been popular in England since Elizabethan times. Especially common on the Parliament side, as we might expect, was the arm and sword issuing from a cloud, symbolising God's help in war (A2, C5, F2-6, G4). The anchor and cloud, conveying hope in heaven, was used both by Sir Arthur Heselrige (B4) and Sir William Constable (C3). Conveniently, the anchor was also the heraldic badge of Constable's traditionally naval family. Another common "Emblem" used was the skull and laurel wreath conveying "death or glory" (F5), and F2 includes the pelican wounding itself to feed its young, symbolising self-sacrifice. Apart from these stereotyped Emblems, both sides adorned their cornets with what can only be described as cartoons (A5, C1, E3, E6), a practice that seems to have grown up at the time of the Bishops' Wars of 1639-40 against Scotland. These cartoons depicted subjects religious, political, or just plain insulting to the other sidefor the latter see especially the royalist cornets described in the next article- and were often extremely complicated.

Predictably, the message conveyed by the emblems, cartoons and mottoes of Parliamentary standards often concerned religion. Many asserted the righteousness of the cause, including A3, whose motto may be translated as "We Shall Win with Christ's Leadership and Guidance"; D1 "God with Us"; D2 "Triumph in the Truth"; D5 "Under Christ's Guidance"; E2 "God For Us"; F3 "We Shall Win with Christ's Guidance"; and G2 "if God is With Us, Who Shall Be Against Us". Others proclaimed the supreme importance of the Bible- "God's Law"- in church and state, a point then much at issue: such are B2 "The Supreme Law is the people's safety"; C5 where "The Word of God" and "The People's Law' are shown opposed to the Kingly power; D6, showing the Word of God triumphing over a Papal crown and Catholic rosary; F3 and H4 “For the Gospel". Other religious themes appear in C4, E3, E5 and F6.

At the beginning of the war "political" standards frequently emphasised the Parliamentarians' declaration that they were fighting, not against the King, but for the just combination of "King and Parliament" in the government of England: thus B5; B6 "For God, King and Country"; C2 "For King and Truth"; E4 "For the King and the Laws Equally". The desire for a "just peace" is expressed in A5 "We All Offer You Peace"; D3 (a Biblical quotation); G3 "We Fight for Peace"; G4 "For Peace and Truth"; H5 "Fighting For a Wounded Nation". Others were more belligerent (A2 "Watch out, we're here" and H6) and C1 is aimed at the Anglican clergy, who wore square caps like "mortar boards": with the motto "The Square Shall Be Made Round", the soldier is cutting off the corners of such a cap, changing the "Squarehead" into a "Roundhead"! Most aggressive of all is E6, a late specimen advocating the execution of the King, an idea not entertained until 1647.

Some few Parliamentarians used devices of a purely heraldic and personal nature, such as the Earl of Essex's family motto "Virtue Attracts Envy" on a standard of his orange livery colour (A1), Lord Grey's ermine unicorn (B1), Constable's anchor (C3) and the black horse badge of Captain Nelthorpe (G5). Space allows us to show here only about one third of the parliamentary cornets known: the standards of the independent troops of 1642 are particularly well recorded.

The Earl of Essex's Army, 1642-5

Essex's Regiment of Horse

A1. Colonel's troop of Lifeguard: r. from the gentlemen of the Inns of Court, many of its "troopers" became colonels or generals. At Edgehill this troop wore complete cuirassier's armour like that of Heselrige's "Lobsters".

A2. Troop colour

A3. Troop colour -Captain Chute. Under the command of Sir Philip Stapleton, Essex's horse served in most of his campaigns, including Edgehill, Turnham Green, 1642; 1st Newbury, 1643; Cornwall, and 2nd Newbury, 1644. In 1645 it became part of the New Model, the Lifeguard becoming Sir Thomas Fairfax's Lifeguard and the remainder going into Graves' regiment.

A4. Williarn Russell, Earl of Bedford personal colour.

General of the Parliamentary Horse at Edgehill in 1642, he also besieged Sherborne Castle in that year, but in 1643 defected to the royalists, only to surrender in 1644.

Sir William Balfour's Regiment

One of the best of Essex's cavalry regts., it fought at Edgehill, 1642; 1st Newbury, 1643; Cheriton, Cornwall and 2nd Newbury, 1644.

A5. Colonel's colour- Sir William Balfour was Lieutenant General of Horse at Edgehill, where he greatly distinguished himself.

A6. Capt. (later Major) Balfour- son of Sir William.

B1. Thomas Lord Grey of Groby's troop.

This troop fought under Balfour at Edgehill, but afterwards followed Grey to the Midlands, where it served 1643-4: also at 1st Newbury, 1643.

B2. Sir Samuel Luke.

The troop fought with Balfour at Edgehill, but in 1643 Luke became Governor of Newport Pagnell, Bucks, and his troops operated from there in 1643-5, including the capture of

Hillesden House, Bucks, and an action at Islip, Oxon, both in 1644. Luke was also Scoutmaster-General, or head of military intelligence, to Essex's army.

B3. Arthur Goodwin's Regt- colonel's standard.

Goodwin was MP for Bucks, where his regiment was raised s. Edgehill, Hants, Berks, and Wilts, 1642; Brill, Reading, 1643. Disb., 1643, on Goodwin's death.

Sir William Waller's Army, 1642-5

B4. Sir Arthur Heselrige's Regt- colonel's colour.

The famous "Lobsters", so-called because of their complete suits of armour, were raised by one of the "Five Members". s. with Waller at Lansdown, Roundway Down, 1643; Cheriton and Cropredy Bridge, 1644. Taken into New Model as Butier's. s. at Naseby, Berkeley, Bristol, 1645: afterwards Horton's, see below (F1-6).

B5. Sir Michael Livesey's Regt- colonel's colour.

r. Kent. s. Chichester, 1642, Cheriton, Cropredy, 2nd Newbury, 1644, became Ireton's in New Model (see below E5). Livesey was described by his major as "a most notorious coward and a penurious, sneaking person".

B6. Captain Edward Kightly- troop colour.

Arrived too late for Edgehill. Killed at Chewton Mendip, 1643, probably serving in Waller's own regiment of horse.

C1. Col. Edward Cooke's Regt- colonel's

colour.

s. Cheriton, Cropredy Bridge. Lord Fairfax's Northern Army, 1642-5

C2. John Lambert's Regt.- colonel's colour.

Lambert's cavalry fought in most of the northern campaigns, notably at Adwalton Moor and Hull, 1643; Nantwich, Selby and Marston Moor, 1644. In the New Model, Lambert served as Colonel, General and Cromwell's right-hand man.

C3. Sir William Constable's Regt- colonel's colour.

Operated mainly in north and east Yorks, in actions at Bridlington, Whitby, Scarborough, Driffield and Marston Moor, 1644. Constable also had a foot regiment.

C4. Captain Copley of Doncaster-troop

colour.

Regiment uncertain, but the troop was at Adwalton Moor, 1643.

C5. James Mauleverer's Regt- colonel's colour.

s. Fairfax's campaigns including Marston

Moor.

C6. Captain Nathaniel Barton of

Derbyshire- troop colour.

Originally a chaplain, Barton served under Sir John Gell and Lord Fairfax, and later as a major in Scroope's regiment of the New Model Army. Forces in the West Midlands and Wales, 1642-7

D11. Sir William Brereton

- colonel's colour.

Brereton was C-in-C. of Cheshire, and an excellent soldier. Among his many actions were Nantwich, Hopton Heath, 1643; Montgomery, 1644; Denbigh and Lichfield, 1645.

D2. Sir Thomas Middleton - colonel's colour.

C-in-C North Wales, he often co-operated with Brereton. s. N. Wales, 1643; Oswestry and Montgomery, 1644.

D3. Thomas Mytton's Regt.- Major Castleton's troop.

Mytton commanded in Shropshire.

s. under Middleton and in 1645 took over his command. Took Shrewsbury, 1645; in Wales, 1645-7.

D4. Robert Lord Brooke - personal standard. An influential nobleman, he garrisoned Warwick Castle in 1642 and fought at Southern. Killed at Lichfield, March, 1643, by a sniper. Forces in Wilts, and Dorset, 1642-5.

D5. William Sydenham's Regt. -colonel's colour.

An active soldier, Sydenham was governor of Poole and Weymouth, and s. principally in Dorset.

D6. Sir Edward Hungerford's Regt - Major Ludlow's troop.

Ludlow served in Essex's Lifeguard (see A1) before becoming Major of the regiment of the incompetent Hungerford: as such, he defended Wardour Castle, 1643. Later served as a colonel in Waller's army and a general in the New Model. Various Forces, 1642-5

E1. Francis, Lord Willoughby of Parham - personal colour.

C-in-C. in Lincolnshire, 1643.

s. Gainsborough. Retired in 1644.

E2. Sir John Meldrum - colonel's colour.

A Scottish professional soldier, Meldrum served in many theatres of war. At Hull and Portsmouth, and Edgehill, 1642; Reading, Hull and Lincs, 1643-4, Selby, Newark and Lancs, 1644. Killed at siege of Scarborough, 1645.

The Earl of Manchester's Army, 1643-5

Oliver Cromwell's Regt.

r. East Anglia, growing out of a single troop raised in 1642 to a double-sized regiment of 14 troops.

s. Winceby, Gainsborough, 1643; 2nd Newbury, Marston Moor, 1644.

E3. Captain Swallow's troop-"The Maiden Troop".

r. at the expense of the ‘young men and maidens’ of Norwich, hence the symbolism and motto “Burning with the care of Zion".

E4. Capt. James Berry's troop.

Berry was Cromwell's own lieutenant before getting a troop of his own. Afterwards a Major in Twistleton's (see G2), a Colonel and a Major-general. In 1645 Cromwell's regiment was split into two New Model units, half the troops (including Berry's) joining Fairfax's Regt. and half (including Swallow's) forming Whalley's Regt. These two units

s. Naseby, Langport, 1645; Colchester, 1648; Dunbar, 1650;

Worcester, 1651.

The New Model Army 1645-60

E5. Henry Ireton's Regt.- Colonel's colour. Ireton, Cromwell's son-in-law, took over Livesey's Regt. (see above) in 1645. Under him it s. Naseby, Bristol, 1645; Oxford, 1646; Colchester, 1648. Part of it joined the mutiny at Burford in 1649.

E6. Thomas Harrison's Regt - Major William Rainsborowe's troop (c. 1648). The regiment (formerly Sheffield's)

s. Naseby, Bristol, 1645; Cornwall, 1646; Preston, 1648. Rainsborowe's standard urges the execution of the King, with the motto “Safety of the people is the supreme law". Brother of the famous Leveller leader Thomas Rainsborowe (or Rainsborough), William was also an extreme radical, dismissed for sedition in 1649.

Colonel Thomas Horton's Regt. (after 1647).

Formerly Butler's, formerly Heselrige's (see above) s. S. Wales and St. Fagan's, 1648; Ireland 1649.

F1. Colonel's colour.

F2. Major Thomas Penyfeather - s. as a captain under Heselrige.

F3. Captain Essex.

F4. Captain John Godfrey.

F5. Captain Elijah Greene.

F6. Captain Arnall.Col. Philip Twistleton's Regt. (after 1647).

r. Lincs. by Col. Edward Rossiter, and fought under him at Naseby, 1645. Twistleton, Rossiter's major, became colonel in 1647 and with him the regiment.

s. Preston, 1648; Dunbar, 1650; Scotland, 1653-4; Penruddock's Revolt, 1655; disb. 1659.

G1. Colonel's colour.

G2. Major James Berry.

G3. Captain Pearte- s. under Rossiter.

G4. Captain Owen Cambridge.

G5. Captain Nelthorpe -s. under Rossiter.

G6. Captain Haines.

Col. Augustine Skinner's Regt. (the Kentish Horse).

r. Kent 1647-8. Not strictly part of the New Model, it probably contained elements of Sir Michael Livesey's Regt. in which Skinner served. Helped to suppress Kentish rising in 1648.

H1. Colonel's colour.

H2. Captain Owen.

H3. Captain Peak.

H4. Captain Scott.

HS. Captain Robert.

H6. Captain Gibbons.

The Royalist Horse

The very nickname 'Cavalier' signified a horseman, and the King's cavalry was, from the first, the most effective arm of his forces: playing a leading role in the Royalist successes of 1642-44, it eventually met its match in Cromwell's Eastern Association horse, and, after Marston Moor, was increasingly outclassed by its better equipped and more disciplined Parliamentary opponents. Essentially feudal and aristocratic in composition, the King's horse had its origins in the well-mounted troops of volunteers raised from 'noblemen, gentlemen and their followers' at the beginning of the war. Unlike their Parliamentarian counterparts, which were, for a time, left to operate independently, these Royalist troops were at once organised into regiments.

Regimental strength was nominally five hundred, but only prestigious units like the King's Life Guard or Prince Rupert's Horse ever seem to have reached this target, and in the early years of the war a normal Royalist horse regiment consisted of six troops of around seventy men each, a total of about four hundred riders. By 1644, when things had begun to go badly for the King, even the stronger regiments (like Wilmot's and Prince Maurice's) were down to three hundred men, and the weakest ones - which had only two or three troops - could muster no more than eighty; later still in the war, troops were down to twenty men each, and three or four 'regiments' had to be amalgamated to make up a worthwhile unit.

Regiments were normally commanded by a colonel- who might also be a general, in which case his position was more or less honorary- assisted by a lieutenant-colonel and a major. These three 'field officers' also commanded troops- effective control over the colonel's troop being exercised by a captain-lieutenant – and the remaining troops of the Regiment were headed by captains. Each troop also had a lieutenant, a cornet to carry the standard, a commissioned quartermaster, three corporals and (in theory, at least) two trumpeters, a farrier and a saddler.

Though full of spirit and often excellently horsed from gentlemen's stables, the Royalist cavalry were not always well-equipped, and at first ... 'the officers had their full desire if they were able to procure old backs and breasts and pots (helmets, either single or triple barred) with pistols or carbines for their two or three first ranks, and swords for the rest; themselves (and some soldiers by their example) having gotten, besides their pistols and swords, a short pole-axe'. Such pole-axes, useful for in-fighting against armoured opponents, seem to have gone out of general use fairly early in the war.

Body armour was not always worn, and hats frequently served instead of helmets, but protective leather buff-coats were almost universal amongst the cavalry on both sides. They were, indeed, probably the only kind of ‘uniform' worn by most horse regiments, though some cavalry units may just possibly have had coats of a uniform colour, and others may conceivably have identified their members by like-coloured ribbons or sashes. A troop raised by the Earl of Newcastle just before the beginning of the war is known to have embellished its horses with knots of ash coloured ribbon, but whether such fol-de-rols survived the rigours of campaigning is less certain. Some of the more aristocratic Royalist units- notably the King's Life Guard, known as the 'Troop of Show'- were certainly magnificently clad, but it seems likely that these, being gentlemen, would have worn their own splendid civilian clothes. Cavalry officers, at any rate, did so at all times.

Trumpeters, as in later times the focus of unit pride, wore a distinctive coat with hanging sleeves. Such coats, like the banners on their trumpets, might well be in the livery colour of the troop or regimental commander- no doubt they were provided at his expense- and might also be decorated with his personal device. The trumpeters of Sir Richard Astley's troop, carved on a panel on his tomb at Patshull, Staffs, certainly have their trumpet banners blazoned with the pierced cinquefoil (a five-leaved flower) from his family arms. Over and above unit identifications, Royalists habitually wore red or rose-pink sashes; their opponents in Essex's army wore orange-tawny ones, and these seem to have been in fairly general use amongst all Parliamentarians during the early years of the war. There is some evidence, nevertheless, that Lord Fairfax's northern army wore blue sashes, and rather more that the New Model - confusingly – adopted crimson ones. Deception was, therefore, a relatively easy matter, and Colonel Henry Gage's Royalist troopers 'disguised themselves in Orange-tawny scarves' for their ride through enemy territory to the relief of Basing House in 1644.

To make confusion twice confounded, the cavalry standards (or 'cornets') of the opposing sides were exactly similar in type, being roughly two feet square and made of fringed and painted taffeta. Each troop carried one, and the basic colour of standard and fringing was the same within the regiment. Royalist cornets are far more sparsely and haphazardly recorded than those of their enemies, for whereas several books of Parliamentarian standards survive, I know of only one scanty and partially illustrated list made by a Cavalier.

Thomas Blount, it is true, describes the devices of certain Royalist standards in his 'Manner of Making Devices' (published 1650), but unfortunately fails to mention their colours (see list at end of article). Most of the cornets shown here, therefore, are trophies taken by the Parliamentarians and recorded by them. The accidental nature of the survivals makes it impossible to say whether there was any set rule for differencing standards with Royalist regiments of horse. The Queen's Regiment (A2-3) seems to have had cornets of the same basic pattern, while Arthur Aston's (D3-4) regiment used varying numbers of crosses to distinguish between troops, and those of Sir Horatio Cary (E1-2) at least share the same rude sentiment.

The most splendid recorded Royalist cornets, as one might expect, are those of the King's and Queen's Regiments (A1-3), and some noblemen appear to have borne their full arms on their troop standards (B1, D1), a practice unknown on the Parliament side. The vast majority of Royalist cornets, however (like those of their enemies), display a motto on a scroll, in many cases accompanied by a kind of 'political cartoon'. The sentiments conveyed are various.

Some express simply loyalty to the crown (A5, B4, B5, D2), or uphold the Divine Right of Kings (C3, D5, F1). Others hope for peace (B2, C5), but more are belligerent or defiant (C1, C4, E4, F2, F4) and some specifically abuse Parliament and its supporters (A4, D5, F3). ‘Cuckolds we come'- an insult which never failed to amuse the Cavaliers- referred to the unfortunate marital experiences of the Earl of Essex, Parliament's commander-in-chief from 1642-5 (E1-2, F5). C2, by contrast, was as pious in its religious sentiments as any Parliamentary cornet.

A1 King's Lifeguard of Horse: troop

colour?

This standard is distinguished from all the rest by its unusually deep gold fringe, as befits its special status. The royal device may have been embroidered rather than painted. The regiment served in most of the principal actions of the war, including Edgehill, 1642, Newbury, 1643, Cropredy, Cornwall, 2nd Newbury, 1644 and Naseby, 1645.

A2-3 The Queen's Regiment of Horse:

colonel's colour and troop colour. These 'French' standards honour the nationality of Queen Henrietta Maria, whose regiment did, in fact, contain a number of Frenchmen, though it was mainly recruited from Lancashire Catholics. One of the toughest and most efficient Royalist cavalry units, it was formed in 1643 and served at Aldbourne and 1st Newbury, 1643, Cheriton and 2nd Newbury, 1644, Naseby, 1645. In November, 1645, it was decimated at Shelford House, near Newark, after refusing to accept quarter.

A2 was probably taken at Aldbourne, but

A3 (inserted here for comparison) was lost at Naseby.

A4 Sir John Culpepper's troop- probably Lord Spencer's Regiment.

The nominal commander of this troop served as the King's Chancellor of the Exchequer and was no soldier. His cornet was taken at Cirencester on September 15th, 1643, when Essex surprised and captured two complete Royalist cavalry regiments, those of Henry Lord Spencer and Sir Nicholas Crispe. The device is, presumably, the Parliament house decorated with severed heads: motto - 'As it is outside, so it is inside', or more plainly, 'Traitors Without, Traitors Within'.

A5 Captain Lumby's troop-probably Sir Nicholas Crispe's Regiment. Also taken at Cirencester, see above A4. Motto: For the King and the Known Laws of England.

B1 Henry Lord Spencer's Regiment

colonel's colour.

See A4. Spencer himself avoided capture at Cirencester, but was slain shortly afterwards at 1st Newbury. Note: The following five cornets were all taken at 1st Newbury.

B2 Unknown.

Motto: We Live By This (i.e. peace) We Die By This (i.e. the sword).

B3 Unknown.

Motto: Always Upon The Square. Obscure, perhaps expressing a preference for dice over Roundheads.

B4 Unknown.

'Long Live the King'.

B5 Unknown.

'God Give the King Both'- i.e. the crown and the victor's laurels.

C1 Unknown.

'It is better to die in battle than to see our wicked people'.

Other Royalist cornets taken at 1st Newbury (no colours given) were: A harp with a crown: motto: 'Lyrica Monarchica'. An Angel with flaming sword treading on a dragon: motto: 'Quis Ut Deus' (probably Col. Morgan's Regiment). One with a motto: 'Courage Pour La Cause'.

C2 Unknown.

Biblical quotation: arms of Rogers family of Dorset.

C3 Unknown.

Motto: in effect: 'Keep Your Hands off the Crown, you fool'.

C4 Troop colour- Henry Lord Spencer's

Regiment?

Taken at Cirencester, see A4. Motto: 'Who Follows This Wins'.

C5 Major Wormesley's troop - Sir Nicholas Crispe's Regiment.

Taken at Cirencester, see A4. Religion mourning over the destruction caused by war. Motto: I Hope for Better Things'.

D1 Unknown.

Possibly a trumpet banner, and illustrated with the fly at the top. Arms:? Leigh quartering Minterne, Dorset.

D2 Unknown.

'For the King'.

(b) Cornets from a muster list of Royalist forces, 10th April, 1644.

D3-4 Sir Arthur Aston's Regiment - 1st and 3rd captains' troops.

The colonel's colour of this unit was apparently plain black, and the 2nd captain's troop had two crosses. Aston, an unpopular man, was Major-General of Dragoons at Edgehill, 1642, and Major-General of Horse in 1643. He was Governor of Reading, 1643, and of Oxford, 1643-4.

He came to a nasty end after the siege of Drogheda, 1649, when his brains were beaten out with his own wooden leg. The regiment served at the capture of Bristol and at 1st Newbury,1643.

D5 Sir Charles Gerrard's Regiment

Colonel's cornet.

The motto indicates a contempt for 'Round' heads. Regiment served Edgehill, 1642, Bristol, 1st Newbury, 1643, Relief of Newark, 1644, S. Wales, 1644-5, Rowton Heath, 1645.

E1-2 Sir Horatio Cary's Regiment Colonel's and Major's cornets.

The motto recalls the old gibe at Essex, and the creature looking out of the barrel may be intended to represent the earl's badge of a reindeer. This regiment was formerly Lord John Stuart's, but its colonel was killed at Cheriton, 1644, and Cary (a turncoat) took over. His command of it was brief, and it soon passed to the Earl of Cleveland, who led it at Cropredy, Cornwall and 2nd Newbury, 1644.

E3 Sir George Vaughan's Regiment

Colonel's comet.

Raised in Wiltshire, this unit served at Lansdown, Roundway Down and Bristol, 1643, Cheriton and Cropredy, 1644. It probably took some hard knocks and by 1644 was reduced to 80 troopers.

(c) Cornets taken at Marston Moor, 2nd July, 1644 - all unidentified.

E4 - 'Terrible As An Army Arrayed'.

E5 - `Touch Not Mine Anointed Ones'.

F1 - 'The Fourth Shall Be Eternal' - the three crowns shown are of England, Scotland and Ireland, the fourth was to be a heavenly one.

F2 - 'This Shall Untie It- i.e. The Gordian Knot of politics.

F3 - 'How Much Longer Will You Abuse Our Patience' - the lion is the King, the beagles are M.P.s led by John Pym, and the larger dog is Kimbolton, leader of the opposition party in the Lords and later Earl of Manchester.

(A colour taken by the Scots had 'a round head and axe' with the motto 'Fiat Justitia')

(d) Cornets taken at Naseby, 14th June, 1645.

F4 - 'I will die rather than turn aside'.

F5 - No doubt the cornet 'which, being one of the first colours taken, the word was, on the pursuite, returned to the enemy with much mirth and scorne'. Colours of some Royalist cavalry cornets in April, 1644 (no devices recorded). Earl of Northampton's Regiment - four blue colours.

Henry Lord Percy's - seven red colours.

Col. Thomas Howard's - eight green colours.

Col. Sir Edward Waldegrave's - three white.

Col. Humphrey Bennett's - red.

Col. Gerald Croker's - two green.

Col. Neville's, formerly Earl of Caernarvon's five red, perhaps with same device as F3.

Col. Dutton Fleetwood's - red.

Sir William Clarke's - three yellow.

Sir Edward Stawell's - two white.

Col. Gunter -two black.

Cornet-devices of some prominent Royalists (colour of standards unknown).

Marquis of Winchester: Motto only 'Aimez Loyante'.

Marquis of Montrose: Laurel wreath and motto 'Magnis aut excidium ausis'.

Lord. Capel: Crown and sceptre, motto 'Perfectis Simae Gubernatio'.

Lord Lucas: Crown and motto 'Dei Gratia'.

Sir Marmaduke Rawdon: A spotted dog? Motto: 'Malem Mori Quam Tardari'

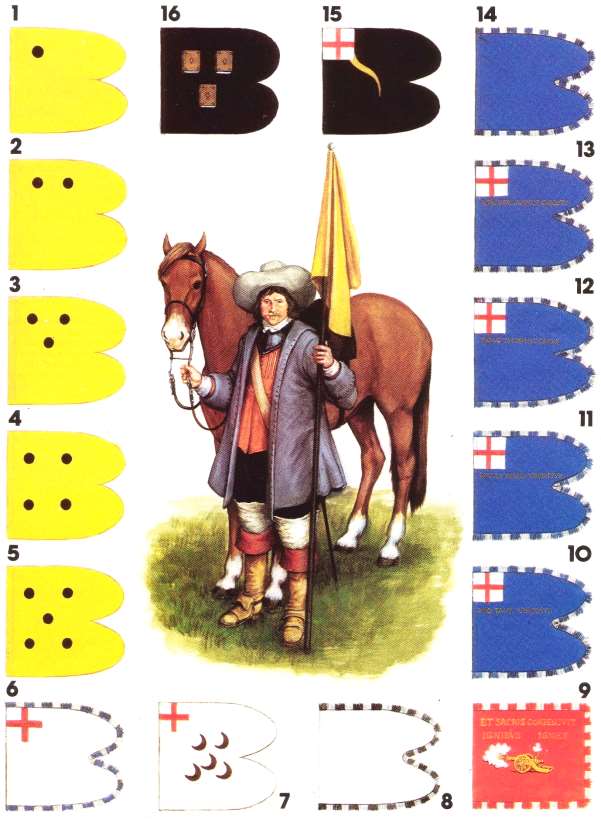

Dragoons and Auxiliaries

Dragoons

The word 'dragoon', which has come to signify a cavalryman, had a rather different meaning in the seventeenth century. The 'dragooners' of the Civil War were simply mounted musketeers- a 'kind of footman on horseback' - combining the nobility of horsed troops with the steadiness and firepower of infantry. "They ought to be taught to give fire on horseback," declared Sir James Turner, "but their service is on foot," and they were organised into files of 11 men, of whom ten dismounted to fight while the 11th held their horses. Their qualities made them ideal for outpost work and for 'the maintenance or surprising of straight (narrow) ways, bridges or foords', and on campaign we find them 'constantly quartered in the van of the whole army'. In sieges their ability to ride to vulnerable parts of the defences and then assault on foot also made them useful, and Colonel Henry Washington's Royalist dragoons (7,8) were the first unit to penetrate the outworks of Bristol in July 1643. Colonel Okey's New Model dragoons (who according to one of their own officers 'were always counted the best men of the army') also showed great enterprise at the taking of Bath in 1645. Crawling on their stomachs up to the gate, they seized the barrels of the enemy muskets protruding from its loopholes, which so demoralised the Royalists that they abandoned their position and allowed the dragoons to set fire to it.

In battle dragoons were generally used to line hedges and ditches on the flanks of the main armies, or else as a mobile striking force. At Marston Moor, for instance, Fraser's Scots dragoons began by clearing away a body of musketeers posted in a ditch to impede the Parliamentary advance, and later joined in the attack on Newcastle's obstinate Whitecoat infantry- when 'their shot made a way for the horse to enter and put them to the sword.' The most famous dragoon action of the war, however, was that of Okey's men at Naseby, which well illustrates the adaptability of this type of troops. When the rival armies came within sight of each other, the dragoons were stocking up with ammunition some half-a-mile away, but Cromwell ordered them to occupy a line of hedges at right angles to Parliament's left flank, and they at once rode to do so. Leaving their mounts with horse-holders they opened up an enfilading fire on Rupert's cavalry as it charged past the opposite side of the hedge, and then beat off an attempt by enemy horse to carry their position. Later, when the battle hung in the balance, they remounted and charged sword in hand to complete the rout of the Royalist infantry, finishing up by chasing a regiment of regular enemy horse off the field and pursuing them almost to Leicester.

The equipment and organisation of civil war dragoons reflected both the need for versatility and their position half way between cavalry and infantry. Their principal weapon, ideally, was a short musket fitted with a snaphaunce or flintlock and attached by a swivel to a wide belt slung over the shoulder: it could then be fired from horseback if necessary. In the 1620s these arms were called 'dragons' (hence 'dragoons') and were stated to have been 16 inches long in the barrel and of the same bore as a musket: in 1644, however, it was recommended that they should have a rather wider bore than the infantry weapon. Okey's New Model dragoons were certainly equipped with snaphaunces, but others, especially amongst the Royalists, had ordinary matchlocks, which could only be conveniently fired when dismounted. Swords were also in general use, but pistols were apparently rare. German dragoons are known to have carried mattocks and spades (to help in the construction of field fortifications) strapped to their saddles, and no doubt some of their English counterparts followed their example: none, certainly, would have been without the recommended 'sacke for necessaries'.

Apart from, perhaps, a pair of riding boots, or occasionally a buff-coat, dragoons seem to have dressed exactly like the musketeers of an infantry regiment. Like these, they will have worn coats of a uniform colour within the unit but (though Okey's men almost certainly sported the 'Venice red' of their colleagues in the New Model Foot) we cannot discover any reliable information concerning the colours worn by other dragoon regiments.

Officers, following the normal practice of the Civil War, wore their own civilian clothes. The horses - or 'nags' - supplied to dragoons are described as 'ordinary', and in some cases this was probably a compliment. Required only for transport, dragoon mounts were more likely to be commandeered cart-horses than spirited chargers, and the New Model allowed for their purchase only half the sum needed to buy a cavalry horse. This inferiority in status to cavalry was also reflected in pay: an ordinary dragoon receiving 1/6d a day, as opposed to 8d a day for a foot soldier and 2/- or 2/6d a day for a cavalry trooper.

Dragoons were organised into troops, ideally numbering a hundred and ten men each - ten files, including horse-holders. Five troops seem ordinarily to have sufficed for a regiment, but the New Model regiment of dragoons had no less than ten. The Colonel, Lieutenant-Colonel (if any) and Major each commanded a troop, the remainder being led by Captains: each troop also had its lieutenant and its 'guidon' - the dragoons' equivalent of a cornet of horse or an ensign of foot - who carried the troop standard. Since dragoons mostly fought dismounted, drums were more appropriate to them than the trumpets of the cavalry, and (in the New Model, at least) two drummers were attached to every troop. Regiments were not always employed en masse, being often split up into units of two or three troops and distributed where their specialist services were most needed. The western Royalist army of 1643, indeed, attached a troop of dragoons to each of its regiments of horse, and Prince Rupert may have adopted this practice in the force he led at Marston Moor (nos. 6,15).

As befitted the half-and-half status of dragoons, their standards or 'guidons' were a cross between infantry colours and cavalry cornets. From the latter they took their small size - about two feet square - and the fringes which some of them feature. The system of differencing troops by mottos, used by Wardlaws Regiment (nos. 10-14) was also a cavalry habit, but dragoons seem more often to have adopted the infantry practice of a plain guidon for the colonel's troop (nos. 8,14), a guidon with a St. George's cross only for the Lieutenant-Colonel (no. 6), and a St. George combined with varying numbers of devices for the remaining troops. Waller's and Luke's Regiments (nos. 1-5 and 16) dispensed with the St. George's cross and used only devices. What made dragoon guidons really distinctive, however, was their swallow-tailed shape. In later years dragoons displayed an inexorable tendency to turn into fully-fledged cavalry, and by the Napoleonic era the transition was complete: the swallowtailed guidon followed them throughout, to be carried to this day by such units as the Royal Scots Dragoon Guards. The true heirs of the old-style 'footmen on horseback', nevertheless, were the regiments of Mounted Rifles raised for the Boer War.

Auxiliary Troops

Artillery as such carried no standards, and none are recorded for the companies of 'firelocks'-armed with flintlock muskets to avoid accidental explosions being caused by the lighted match used by ordinary musketeers- who guarded the various trains of artillery. We know, incidentally, that Waller's six companies of firelocks wore blue coats, while the two companies attached to the New Model (unlike their red-clad colleagues in the Foot) wore 'tawny'. Lord Hopton's Lifeguard of Horse, who bore a gun on their cornet (no. 9) in allusion to his office as General of the Royalist Ordnance, were of course, an ordinary cavalry troop. Parliament's navy occasionally landed parties of armed sailors to stiffen the garrisons of beleaguered coastal towns, most notably at Hull and Lyme Regis in 1644. These wore no uniform, though grey (rather than blue) coats seem to have been popular amongst seventeenth-century mariners. The sailors at Lyme certainly carried a standard: this was probably taken from their ship, and if so is likely to have been rather large, with a St. George's cross in the top left-hand corner and a field of horizontal stripes in contrasting colours.

1-5. Sir William Waller's Regiment of Dragoons (Parliamentarian).

This regiment served throughout Waller's campaigns, including the battles of Lansdown and Roundway, 1643. Despite this, it was up to full strength of over 500 when it mustered in London in September 1643. Afterwards served with Waller at Alton and Basing House, 1643, and at Cheriton and Cropredy, 1644.

1. Major Archibald Strachan's Troop.

2. Capt. John Clerte's.

3. Capt. Nicholas Moore's.

4. Capt. John Bennett's.

5. Capt. William Turpin's.

6. Royalist Lieutenant-Colonel's (?) guidon taken at Marston Moor.

Rupert seems to have had no full regiment of dragoons at Marston Moor, but probably attached troops of dragoons to his regiments of horse.

7. Royalist Captain's guidon.

8. Royalist Colonel's guidon.

Both taken by Essex's forces during the First Newbury campaign, 1643. One or other of these may well belong to Colonel James Ussher's Regiment: this unit served at Edgehill, and, under Col. Henry Washington, distinguished itself at the storming of Bristol, 1643. Afterwards served in the garrison of Worcester.

9. Cavalry cornet of Lord Hopton's Lifeguard troop (Royalist).

Used while Hopton was acting as General of the Royalist Ordnance, 1644.

10-14. Colonel James Wardlawe's Regiment (Parliamentarian).

This regiment, almost entirely officered by Scots, served at Edgehill and on Essex's campaigns in 1643. Wardlawe acted as governor of Plymouth, September 1643- January 1644, and seems to have taken his regiment with him.

14. Col. James Wardlawe's Troop.

13. Lt. Col. George Dundas's.

12. Capt. Alexander Nearne's.

11. Capt. John Burne's.

10. Capt. James Stenchion's.

There was one more company, Capt. Archibald Hamilton's, which had the motto 'Bella Beatorum Bella'.

15. Royalist major's guidon- taken at Marston Moor, see no.6.

16. Sir Samuel Luke's Regiment (Parliamentarian)- Captain's guidon.

Raised in Bedfordshire, 1643, this unit had an unlucky start, being surprised at Chinnor, Oxon, during Prince Rupert's Chalgrove raid, 1643. Three of its guidons, including this one, were then taken. The books are Bibles.

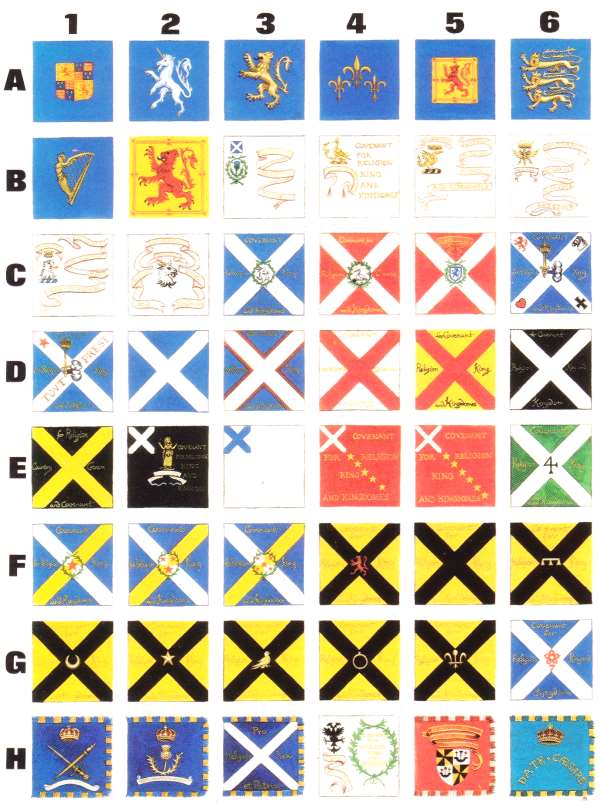

The Scots

The Scots entered the Civil War in 1644 on the side of Parliament, having previously (1639- 40) been in arms against the King. In 1648, however, they changed sides and from 1648-51 they were royalist. Fighting for the King the Scots suffered three major defeats. At Preston 85 colours were lost; at Dunbar 146 and at Worcester 159, including the King's own standard.

These flags were sent as trophies of war to the English Parliament who ordered them to be hung in Westminster Hall where they were carefully recorded and drawn as a 'perpetual memorial to His Highness' (Cromwell's) victories". Throughout the Civil Wars the standard carried by the Scottish Armies was their national flag, the St. Andrew's Cross (D2). Unlike the English who placed their flag in canton, the Scots only occasionally did so (E2-5) preferring to display the saltire in full. This flag, the white saltire on a blue field, was adapted for military use; the colours of the field and saltire being changed for regimental distinction (D2-6). The result is very satisfying and must have presented a brave sight on march or in battle. The "Lion Rampant" on the other hand (B2), was the personal standard of the sovereign as King of Scots. It could be flown by him alone or by his Lieutenant.

Great respect was accorded to this flag. When raised it was greeted by a salute of trumpets, and it was such a royal salute, in 1645, that first warned Argyll that Montrose, the King's Lieutenant, was upon him at dawn at Inverlochy. Scottish colours were 6 1/2 feet by 6 feet square and were made of silk or taffeta. Some, however, were smaller and those of Colonel Scott's Regiment were 5 feet 3 inches by 4 feet 4 inches. The colour-staff generally terminated in a spearpoint, from which hung two long tasselled cords, used to secure the flag when furled. Colours were unfurled in battle - as at Newcastle, where the Scots stormed the walls with 'flyeing collours and roaring drums' - or on the march. It was an offence punishable by death to draw sword in a private quarrel 'while the collours are fleeing', whereas the usual penalty was loss of a hand. Any Scots soldier capturing enemy colours was to have his reward whether there was 'peace or war hereafter', and the penalty for not defending one's own colours 'to the uttermost of one's power' was death.

The battle flags boldly declared the cause for which the Scots fought, though at first there was little uniformity in motto. At Aberdeen, in 1639, Montrose, while fighting for the Covenant, carried a flag which bore the legend "FOR RELIGIOUN THE COVENANT AND THE COUNTRIE" while at the great camp at Duns "everie companie had, flying at the captaine's tent doore a brave new colour stamped with the Scottish arms and this ditton 'FOR CHRISTS CROUN AND COVENANT' in golden letters". At the Battle of Newburn in 1640 the English observed that "embroidered upon their foot colours was the motto 'COVENANT FOR RELIGION CROWNE AND COUNTRY'. At Fyvie in 1644 Argyll's banner (D6)declared FOR RELIGION COUNTRY CROWN AND CONVENANT.

In 1648 the mottos began to be standardised, reflecting the Scots new found loyalty to the King. This state of affairs was confirmed by the Scottish Parliament in 1650 which ordered that upon the "haill culloris and standardes there be COVENANT FOR RELIGION KING AND KINGDOMES". This law was closely observed. The army at full strength bore “10 colours to the regiment and 12 to the major generals". Each regiment carried standards of the same basic colours (D2-6), command of which was frequently given to those from whose territories the forces came. This gave rise to one of the many distinct features of the Scottish system - the liberal use of heraldry. On the colours of both horse and foot there frequently appears the crest or motto of the colonel.

Thus is found the Dove and Snake of Elphinstone (B4), the Dragon of Dumfries (B5), the Thunderbolt of Carnegie (B6), the Lion of Home (Cl), the Goat of Tweeddale (C2-3), the Crane And Stone of Cranston (C4), the Lion of Strathmore (C5), the Maiden of Balfour (E2) and the Double Headed Eagle of Loudon (H4). The flags of the field officers call for special mention. Extremely popular was the use of the all white flag to denote the colonel (B3-6, C1-2). This could carry his crest, the national emblem, the Thistle (B3) or simply be of plain silk. The Lt. Colonel carried an unadorned saltire in the colours of the regiment The major could also do the same - the "stream blazant" not being used in Scotland until the Restoration.

Several colour systems were in vogue in the Scottish Army. In the most common the colonel would display his all white flag (C2) but the individual companies would use the saltire with no attempt being made to indicate the captain (C2, D2-6, E1). All the company colours in such a system were exactly the same. Sometimes the colonel would also use the saltire, in which case his emblem generally appeared on it (F1-3).The difficulties inherent in such a system are obvious and several regiments took a different approach. One was similar to that as used by the English, devices such as stars being used to indicate the captain. When the saltire was in canton, these stars were aligned diagonally from top left to bottom right (E4-5). When, as in most cases, the saltire was employed, the stars appeared at the crossing, generally surrounded by a wreath (F1-3). Saltires, incidentally, seem to have been sewn rather than painted onto the flags. A simpler method was the use of a numeral to indicate the company number (E6).

Lastly, there was a system which seems peculiar to the Scots- the cadency system. In heraldry a particular charge denoted each son of a family in order of seniority. This could be applied to the regiment. Thus the eldest son bore a "label": this would be equivalent to the 1st captain (F6); the second a ‘crescent' = 2nd captain (G1); the third a "star" = 3rd captain (G2); the fourth a "martlet" (bird) = 4th captain (G3); the fifth an "annulet" = 5th captain (G4); the sixth a "fleur-de-lis" = 6th captain (G5); the seventh a “rose" = 7th captain (G6).

Sometimes the charge occurs with a numeral as in (G6) where the seventh symbol a "rose" is reinforced by the number 7. The Horse In 1648 the horse was observed to have "7 colours to the regiment and in every regiment some 500". Such colours could be of very fine workmanship, and, as one Scots captain complained, "cost a great deal"! The device could be left to the individual captain as in the King's Life Guard (H1-3) where each captain was given permission to adorn his cornet with "quhat impresse, rebus or devices they best please, so that they tend to the defence of Covenant, Religion, King and Country".Colonel's cornets were of plain silk, a blue colour of this type being taken at Dunbar, or carried their crest (H4) or arms (H5). Others carried slogans and devices appropriate to the times.

Thus in 1639 when the Scots opposed the introduction of the Book of Common Prayer, the cornets of the Lady Marchioness of Hamilton's troop bore the appropriate impress of "a hand repelling a book". Again, in 1648 when the Duke of Hamilton's army invaded England in support of the King, the Duke's Lifeguard (H6) bore the royal crown and the motto "render unto Caesar". The "arm of God", as might be expected, was as popular in Scotland as in England. A blue cornet taken at Dunbar is a typical example. A gold arm emerges from a cloud grasping a sword, at whose tip is uplifted the laurels of victory. As with the foot, the colours of the horse frequently declared the cause for which the Scots fought - COVENANT FOR RELIGION KING AND KINGDOME.

The Foot

(A1-6, B1) His Majestic's Foot Regiment of His Lyffe Guardes (Lord Lorne's). Colonel: Lt Colonel: Major 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th Captains. Raised in 1650 to attend the King's person; Lord Lorne being appointed colonel. It consisted of 7 companies. As Foot Guards, the men received 2p a day in addition to a normal soldier's wage. Four companies were engaged at Dunbar, the other 3 being with the King at Perth. At Dunbar the companies stood their ground but were, to quote the King, “altogether broken and most of the officers killed or taken prisoner". The colours, however, escaped capture. Lord Lorne and the Foot Guards were on duty in the presence chamber when the King was crowned at Stone in 1651. An attempt was made to repair the damage of Dunbar by making the regiment up to 10 companies of 110 men, each of the "choicest men of the army but it was too late. The King invaded England where the regiment was destroyed at the Battle of Worcester.

(B2) The Royal Standard.

As the King's Lieutenant, Montrose carried this flag throughout his 1644-45 campaigns. Tippenmuir, Aberdeen, Fyvie 1644; Inverlochy, Dundee, Auldearn, Alford, Kilsyth and Philiphaugh 1645. At Auldearn, by his placing of the Royal Standard, Montrose drew the Covenanters into a trap. Thinking that the standard marked Montrose's main position the Covenanters attacked, only to be taken in the flank and destroyed.

(B3) Unknown Colonel. Dunbar 1650.

(B4) Lord Balmerino's. Colonel.

r 1650, destr Dunbar, 1650.

(B5) Lord Dumfries'. Colonel.

r 1648 surnd Preston, 1648 with Lt. Col, one Capt, 5 Lts, 1 Ensgs, 4 srgts and 44 men.

(B6) Lord Carnegie's. Colonel.

r 1640 s Newburn, 1640 disb 1641. r 1648 srnd Preston, 1648 with Lt. Col, 5 Lts, 5 Ensgs, 8 srgts, and 140 men. This mirror image method of writing is a common feature on Scottish Flags.

(C1) Lord Home's. Colonel (Berwickshire Rgt)

r 1648 srnd Preston, 1648 with Lt. Col, one Capt, 4 Lts, 7 Ensgns, 1 Qrt Mst, 14 srgts and 250 men.

(C2-3) Colonel Yester's. Colonel, Company.